(BIVN) – The Kīlauea summit eruption remains paused, and a new eruptive episode is likely to begin within the next 2 to 4 days. The USGS Alert Level is WATCH.

The latest Volcano Watch is about determining magma storage at depth at Kīlauea. The article is written by Charlotte L. Devitre (postdoctoral scholar) and Penny E. Wieser (Assistant Professor) at University of California Berkeley:

Consider a can of soda. When the can is closed (pressurized), the soda contains dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2). When you open the can, the pressure drops, bubbles form and rise. Molten rock (magma) beneath the Earth’s surface behaves similarly and we can learn from the gas trapped in tiny bubbles preserved in crystals from the rock after it’s erupted on the surface.

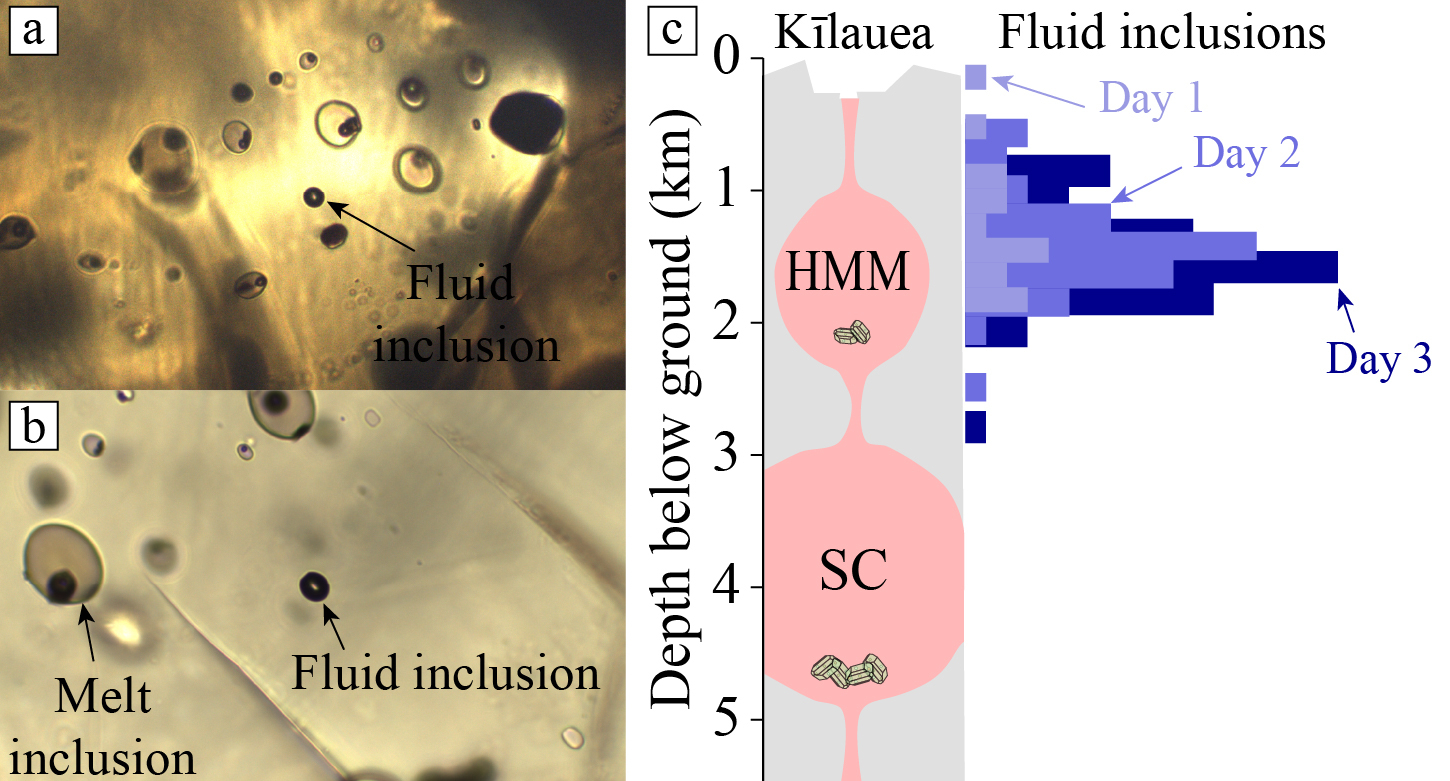

USGS: “Photomicrographs of fluid inclusions trapped inside olivine crystals present in rock samples collected on September 10th, 2023, during a summit eruption of Kīlauea (a-b, on left). Data from these fluid inclusions, collected over three days, reveal that the magmas resided in the shallow Halemaʻumaʻu (HMM) chamber before erupting; the deeper South Caldera magma chamber (SC) is also shown (c, on right).”

As magma rises from 100 km (67 miles) deep beneath the surface, the pressure drops, and bubbles form. When trapped within growing crystals, these bubbles (smaller than the width of a human hair), are called fluid inclusions.

At volcanoes like Kīlauea, the bubbles are primarily CO2. The density of CO2 in a fluid inclusion is sensitive to the pressure the magma was under when the CO2 was trapped in a crystal. The greater the depth (and pressure) the magma was below the surface, the higher the CO2 density, providing a precise record of magma storage depths.

By measuring CO2 densities in lots of fluid inclusions, scientists can determine the depth at which the gas became trapped in crystals, and hence the depth of magma storage before eruption.

USGS: “An HVO geologist makes observations of the vents erupting on the floor of the downdropped block in Kīlauea summit caldera on September 12, 2023.” (USGS photo by N. Deligne)

In September 2023, Kīlauea erupted within Kaluapele (the summit caldera), and a team of scientists from University of California Berkeley (UCB) teamed up with scientists from the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) to carry out a rapid response exercise.

They wanted to determine whether fluid inclusions could be analyzed in near-real-time to provide information on magma storage depths during an eruption. Typically, this type of information is not easy to obtain quickly. If the team of scientists could demonstrate a fast and successful technique for getting this information, it could complement monitoring efforts at many volcanoes.

HVO scientists collected tephra samples and mailed them to UCB. Upon sample receipt, the UCB scientists began their laboratory work around 9 a.m. Pacific Standard Time (PST). They crushed the samples, picked out and polished olivine crystals to find the fluid inclusions, and measured their CO2 densities using a Raman spectrometer.

By the end of the day, around 7 p.m. PST, data from 16 crystals had been collected and analyzed. The data, which was shared with HVO, showed that the erupted magmas had been stored in Kīlauea’s shallowest magmatic reservoir at 1–2 km (0.6–1.2 miles) depth prior to eruption. This depth is relatively typical of small summit eruptions whereas larger eruptions, like the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption, often sample magmas coming from 3–5 km (2–3 miles) depth.

(USGS) The fissure 8 channel carries lava toward the coast on the west side of Kapoho Crater (vegetated cone, far left) in July 2018

In the following two days, UCB scientists continued to collect data to determine whether the results had been biased by the small number of analyses. However, the outcome remained the same, indicating that the results obtained the first day provided a good insight into the storage depth of magma supplying the September 2023 summit eruption of Kīlauea.

This method works well in Hawaii because the magma in our volcanoes contains very little dissolved water, a key to the success of the fluid inclusion work. Many other volcanoes around the world have magmas with far more water, at which the fluid inclusion work would not work. To determine whether this technique could be applied to other volcanoes besides Kīlauea, UCB scientists compiled a large database of analyses of melt inclusions from other frequently erupting volcanic systems in the world, including Iceland, the Island of Hawaiʻi, Galápagos Islands, East African Rift, Réunion, Canary Islands, Azores, and Cabo Verde. Volcanoes in these places are sufficiently “dry” for the fluid inclusion method to be successful.

Ultimately, the study demonstrated that this technique can successfully be applied to provide information on the source depth of the magma erupting at the surface in near-real-time during eruptive events at many different volcanoes globally. Understanding the depth that bubbles were trapped in the crystals, along with other monitoring datasets, can co-inform estimates of the size of an eruption and be used to draw analogues with past eruptions. For instance, in future events at Kīlauea, identifying the contribution of deeper-stored magmas in near-real-time—retrospectively found for the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption of Kīlauea—could potentially be helpful to inform the possibility of the eruption developing into a larger event.

by Big Island Video News6:32 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Scientists can determine the depth of magma storage before eruption by measuring CO2 densities of bubbles trapped in lava.