(BIVN) – A draft environmental assessment for a planned Hawaiian homestead settlement at King’s Landing, where beneficiaries have already been living for 40 years, has been published in the latest issue of The Environmental Notice.

The King’s Landing Kuleana Homestead Settlement Plan (KHSP) “aims to provide beneficiaries who are willing and able to reside on unimproved lands with the opportunity to hold long-term homestead leases,” the draft EA states.

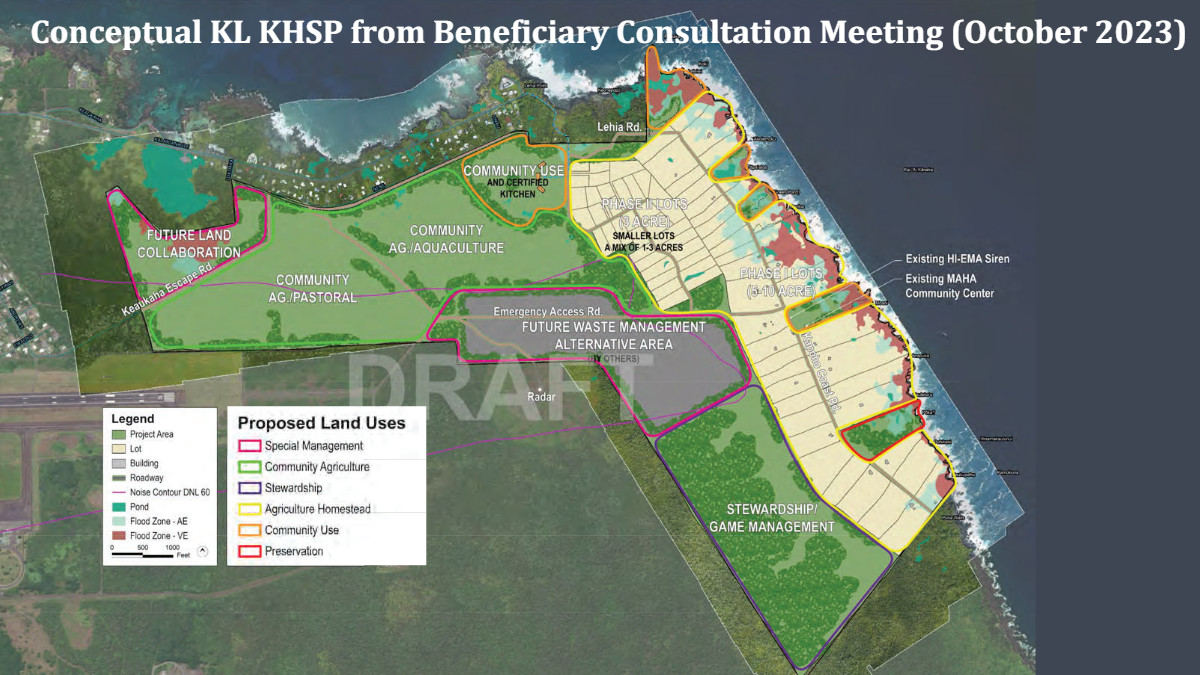

Of the 1,334-acre parcel, the DHHL has designated 398 acres as Kuleana Homestead, accommodating 78 lots. In addition, 364 acres have been designated as Community Use, 332 acres as Community Agriculture, and 240 acres

as Conservation.

Early in the 865-page document, the background of the project, spanning decades, is provided:

The Hawaiian Home Lands Program was started with the passage of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, 1920, as amended (HHCA) due to the efforts of Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole. Passed by Congress and signed into law by President Warren Harding on July 9, 1921 (Chapter 42, 42 Stat. 108), the HHCA provides for the rehabilitation of the native Hawaiian people through a government sponsored homesteading program. Per HHCA Section 201(a)(7), the term “native Hawaiian” (with a lower case “n”) means any descendant of not less than one-half of the blood of the races inhabiting the Hawaiian Islands previous to 1778, or those with 50% and more Hawaiian blood. Native Hawaiian with an upper case “N” refers to all persons of Hawaiian ancestry regardless of blood quantum.

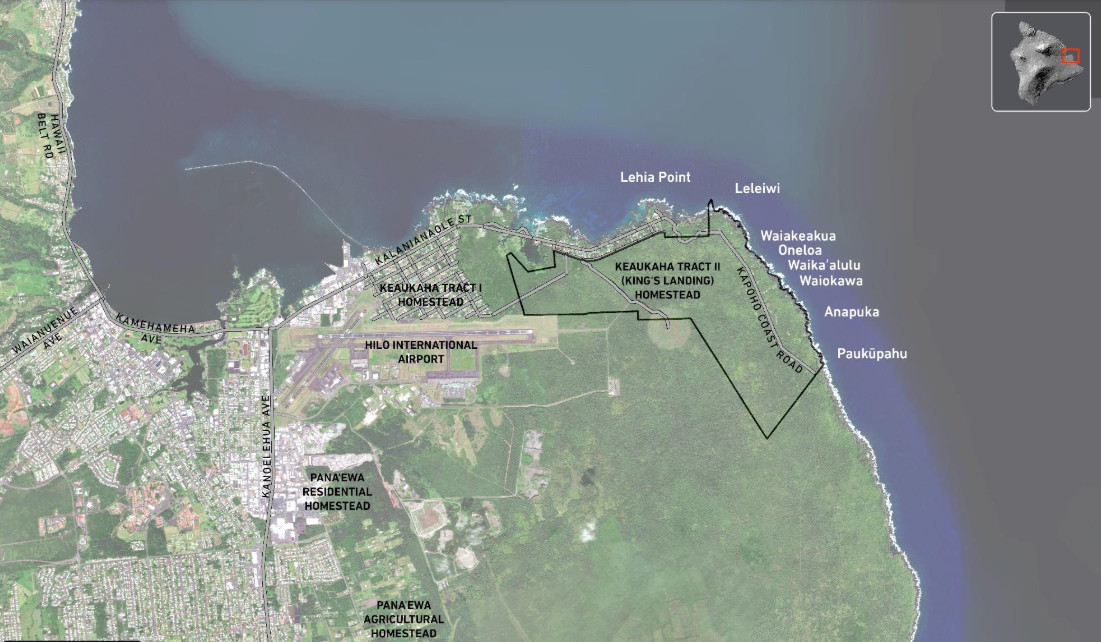

One of the early movements toward community-based self-sufficiency was in Keaukaha, Hawai‘i. Although house lots were awarded at Keaukaha Tract I in 1924, Keaukaha Tract II (King’s Landing) remained “idle”, without house lots awarded. Fishermen, ‘opihi and limu gatherers frequented the coast while swimmers utilized the ponds. A few of the original native Hawaiians of the area continued to reside there with the knowledge and consent of the Commission and the Department.

In the 1950s through the 1970s, disputes arose regarding DHHL oversight of residency in Keaukaha Tract II. Families received verbal approval from staff and commissioners at that time to enhance the area. The Pakani family, for instance, undertook various improvements such as road upgrades, well digging, dredging, land clearing, and cultivation of bananas, taro, and other crops for daily sustenance. However, several years later, eviction notices were issued to these families. Mr. Keli‘i “Skippy” Ioane and his family, after a year of residing at King’s Landing, also received a similar notice of eviction. Mr. Ioane continued to seek a dialogue, even inviting decision-makers to his home. However, DHHL cited the absence of a management plan for the area as the reason for not issuing a lease.

In response, the Ioane and Pakani families continued to persist and established a community association named Mālama Ka ‘Āina Hana Ka ‘Āina (MAHA), which means “taking care of the land, working the land”. Starting in the summer of 1983, more native Hawaiian families moved into King’s Landing. Many of these families showed signs of disillusionment with mainstream Western society. For them, settling at King’s Landing represented a genuine opportunity to forge their own path independently (MAHA, 2023).

Discussions continued between DHHL and MAHA, as DHHL recognized the need for alternative homesteading programs. A Right-Of-Entry (ROE) agreement was proposed by DHHL (ROE No. 76) to give these residents temporary permission to be on the land until a management plan could be created and implemented. A final ROE was signed by the DHHL Chairman in 1986.

Along with Palapala Ink and other partners, MAHA developed a Community Management Plan that was comprised of a Hawaiian vision of land use and subsistence occupancy in 1987 (Palapala Ink, 1987) (see Appendix A). The plan called for alternative homesteading, aquaculture development and a land bank for community-based economic activities on 800 acres of land. It codified an approach to family and community self-sufficiency based on the skills of current residents, and it proposed an affordable “Kanaka Code” (People’s Code) as an alternative to the County of Hawai‘i’s standards.

The Kanaka Code identified development benchmarks over time to ensure building code compliance and to accommodate the incremental nature of financing for those who cannot qualify for or do not want to take on a conventional 30-year home loan. Inspiration came from the historical knowledge of the wahi pana (ancestral place), off-grid systems, and low impact technologies. Completed in 1987, this management plan was submitted to DHHL. The management plan continues to be forwardthinking and supports the needs of the community of DHHL beneficiaries as well as addressing the concerns of DHHL. The plan also called for a separate and distinct subsistence homestead waitlist.

However, the discussions stalled, and the MAHA Community Management Plan was never formally adopted by DHHL. Since the submission of the MAHA Management Plan, the village continued maintenance and management of King’s Landing. The King’s Landing village naturally grew in that time while members of MAHA, such as Mr. Ioane and other MAHA presidents continued to attend Hawaiian Homes Commission (HHC) Meetings to request leases for the King’s Landing beneficiaries. In addition to the residential homesteads, King’s Landing was home to many agricultural businesses, from florists to food producers. Although some economic opportunities have not been as successful as planned, MAHA members today still strive to make a living using the resources surrounding them.

Members of MAHA reside at King’s Landing under a ROE permit. Members are all native Hawaiian applicants on DHHL’s Hawai‘i Island waitlists who have continued to exercise their self-governing and self-determining powers entrusted to them by the HHCA. However, around 1995 other individuals who were non-beneficiaries and non-MAHA members illegally settled in King’s Landing. Over time this has created further challenges to effectively manage these lands and support the efforts of MAHA, which continues to “play by the rules” to seek a long-term lease for the organization and its members, who are DHHL beneficiaries. These types of issues prompted MAHA to reengage more proactively with DHHL and the HHC.

Due to Mr. Ioane’s advocacy, a new ROE (ROE No. 294) was issued to MAHA by DHHL in 2001. This new ROE disposition recognized the desire of more DHHL beneficiaries to live a King’s Landing subsistence lifestyle. MAHA outlined 24 lots to welcome 24 families into the village. By this time DHHL had created a new approach to offer leases for this type of alternative homesteading, called the Kuleana Homesteading Program. However, throughout this time, there has never been a provision of long-term homestead leases to these or other qualified DHHL beneficiaries at King’s Landing.

Under the current ROE agreement, when original beneficiaries that reside in King’s Landing and are listed under the ROE pass away, they are unable to pass along their lands to their dependents, or successors, as would be the process under a typical homestead lease. The lack of successorship rights threatens to further fracture this community as family successors in this situation are often required to relocate, severing their relationship to the ‘āina and impairing the spiritual rehabilitation that exists when kanaka are connected to their ‘āina (MAHA, 2023).

In 2020, MAHA formed a Kūpuna Council. This council was formed so that the leadership roles could be transitioned from the original MAHA Board to their keiki, now adults. The MAHA Board, now led by the new generation and guided by the Kūpuna Council, engaged with the HHC to request regular meetings, and establish a routine of clear and open communication. The objectives of these meetings were: to address trespassing by non-MAHA members and associated issues; to secure successorship and lease agreements tailored to the unique kauhale (village) governance of King’s Landing; and to help familiarize the HHC to the MAHA community and its management plan.

In 2020, the HHC appointed an Investigative Committee (HHC Committee), made up of commissioners for the purpose of identifying possible land security and successorship solutions for King’s Landing. MAHA and the HHC Committee for King’s Landing met and toured all 24 lots within King’s Landing. After the tour, the MAHA Board and the Commissioners agreed to work towards a solution that supports beneficiaries and follows DHHL’s due process. The King’s Landing community seeks to develop solutions that honor the history and success of its original predecessors, including implementing relevant principles and guidelines in the 1987 Management Plan, while recognizing the urgency of time, since they have been waiting for many decades. Eighteen (18) beneficiaries have passed away while residing in King’s Landing and awaiting their leases, and others that continue to reside in King’s Landing are now well into their 70s. There is an urgency for these beneficiaries to have a guarantee that their family will continue to have a place to call home at King’s Landing.

The statutory 30-day public review and comment period on the Draft EA has begun. Comments are due by July 8, 2024.

by Big Island Video News8:53 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HILO, Hawaiʻi - The Department of Hawaiian Home Lands has published a draft environmental assessment for the planned settlement of King's Landing, where beneficiaries have already been living for 40 years.