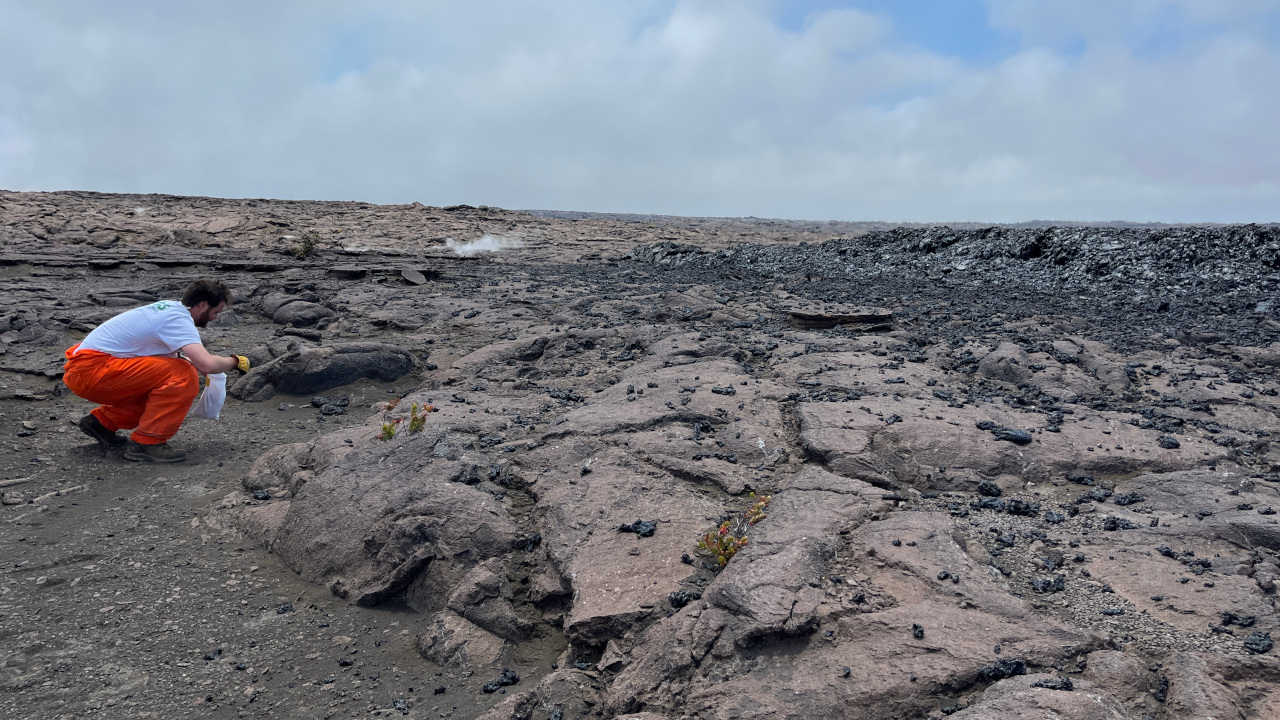

USGS: “On June 3, 2024, HVO field crews collected cooled spatter from the then inactive vents of Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift Zone eruption. Samples are processed in the laboratory to determine their chemistry, which helps HVO scientists understand where the magmas were stored prior to eruption.” (USGS photo by K. Lynn)

(BIVN) – Kīlauea is not erupting, and activity on the Southwest Rift Zone remains paused. Scientists say it is unlikely that the eruption will restart, and the USGS Volcano Alert Level is at ADVISORY.

The USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory has been saying that although the eruption has paused, “additional pulses of seismicity and deformation could result in new eruptive episodes within the area or elsewhere on the Southwest Rift Zone.”

Research Corporation of the University of Hawai‘i seismic analyst Maddie Hawk examined the seismic activity that preceded the latest eruption in this week’s Volcano Watch article:

Kīlauea began erupting from fissures southwest of Kaluapele (the summit caldera) just after midnight on June 3; the eruption ceased just nine hours later, though lava flows continued to slowly spread for several more hours. Prior to the brief eruption, the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) had been monitoring pulses of heightened seismic activity in the summit area for weeks.

How did these earthquakes give us insight into the features of the molten magma below and the eruption that was to come?

Earthquakes result from the breaking of cooler, brittle rock. As magma moves into an area, it forces the surrounding rock to bend and then break. This brittle rock “failure” is what seismologists at HVO see daily on live data streams as earthquakes. The locations of earthquakes can outline magma chambers, indicate fault movement, or show where magma is moving into new area. At Kīlauea, earthquake swarms paired with changes in ground motion as seen on tiltmeters give HVO scientists an idea of the pressurization of magma chambers beneath the surface.

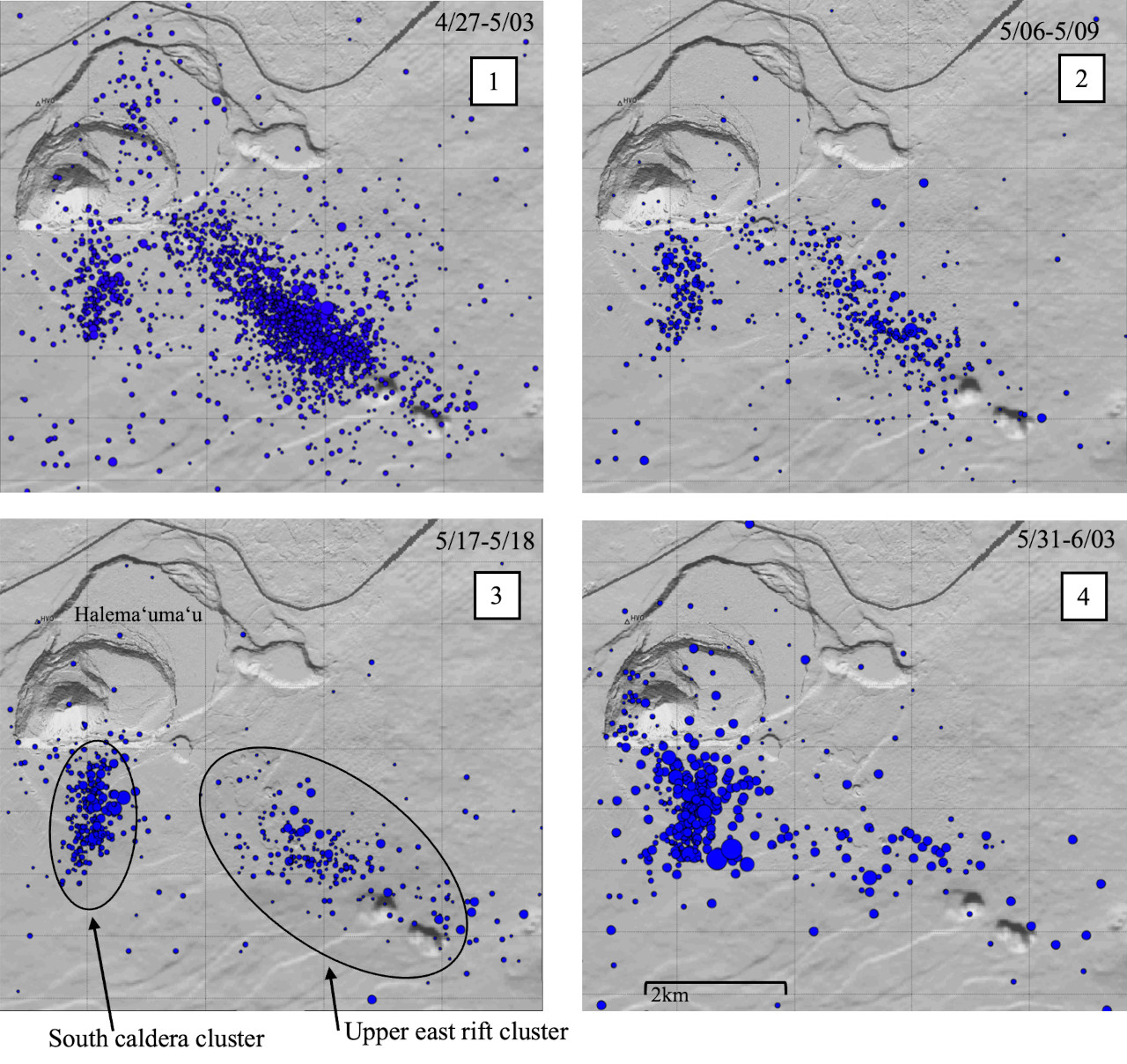

The proposed magma plumbing system at Kīlauea is divided into three main chambers: the Halemaʻumaʻu reservoir, the south caldera reservoir, and the Keanakākoʻi reservoir. In the weeks leading up to Monday’s eruption, there were three distinct periods of heightened unrest. From April 27–May 3, May 6–9, and May 17–18, two distinct clusters of earthquakes occurred in the south caldera and the upper East Rift Zone (see box 3 in Figure 1).

(Figure 1) USGS: “The two distinct clusters of earthquakes at Kīlauea during the four recent time periods of swarm activity. The event counts at the south caldera cluster increase while the counts at the upper East Rift Zone cluster diminish from the first to the fourth time periods.”

During these swarms, earthquake locations often switched between the south caldera cluster and the upper East Rift Zone cluster as magma pressure levels fluctuated within the different storage regions. The event counts at the south caldera cluster increase while the counts at the upper east rift cluster diminish as the system moved closer to eruption. Rates of ground tilt, measured by summit tiltmeters would also increase during the earthquake swarms, indicating an increased pulse of magma was accumulating beneath the surface.

Although the earthquakes occurred in distinct clusters, they could have happened in response to the stresses created by magma chambers located nearby. For this reason, there were several possibilities scenarios. First, magma accumulation could stop, and no eruption would occur. Magma accumulation could continue with an eruption in Kaluapele or magma could migrate to the southwest with either an intrusion (similar to last January) or eruption.

As we now know, magma did indeed migrate to the southwest and this time it erupted.

USGS: “Aerial image of the Southwest Rift Zone eruption of Kīlauea, viewed during an overflight at approximately 6 a.m. on June 3, 2024.” (USGS image)

Just after noon on Sunday, June 2, earthquakes increased again beneath the south caldera region and intensified quickly, prompting HVO to raise the alert level and aviation color code for Kīlauea at 5:30 p.m. HST.

For twelve hours, earthquakes of up to M4.1 shook the summit region until 12:30 a.m. Monday morning, when a fissure opened about 1 mile (2 km) southwest of the caldera. The eruption happened in the vicinity of ground cracks that formed in the late January intrusion.

Past eruptions in this area—in 1971 and 1974—have been brief, so it was no surprise when the fissure stopped erupting nine hours after the eruption began. Fortunately, the short-lived eruption occurred within a closed area of Hawaʻi Volcanoes National Park; it did no damage to infrastructure. This was the first eruption in this area of Kīlauea in 50 years, and the first eruption outside of Kaluapele since 2018. Only about 100 acres were covered with new lava, compared to over 500 during the September 2023 eruption within Kaluapele.

While lava has stopped moving on the surface of Kīlauea, volcanic gas emissions remain elevated and activity beneath the surface remains dynamic. HVO scientists will continue to closely monitor for signs of change.

by Big Island Video News7:37 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Scientists are taking a closer look at how the seismic activity in the weeks before forecasted the June 3 eruption.