(BIVN) – Mauna Loa volcano on the Island of Hawaiʻi is not erupting and webcams show no signs of activity.

The current alert level for Mauna Loa remains at NORMAL. Scientists say ground deformation “indicates continuing slow inflation as magma replenishes the reservoir system following the 2022 eruption”, the start of which is the subject of the latest U.S. Geological Survey article.

From this week’s Volcano Watch, written by USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates:

The 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa occurred late in the evening of November 27th. The eruption was preceded by intense earthquake activity about half an hour prior to glowing lava seen on USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) webcams. How does HVO narrow down the precise time that the eruption started?

Remote cameras are critical to confirm eruptive activity but, in many cases, worldwide, views of the activity can be obscured. Clouds, fog or volcanic gas can block views. Or cameras may not cover the eruption site. Hence, HVO and other global observatories establish numerous methods to attempt to identify eruption activity even if the volcano cannot be clearly seen.

One way to monitor volcanoes is by measuring the sounds of an eruption. These sounds can rapidly travel away from the eruption vent in the same way that a rock thrown into calm water can make ripples that move away from the “plop point.”

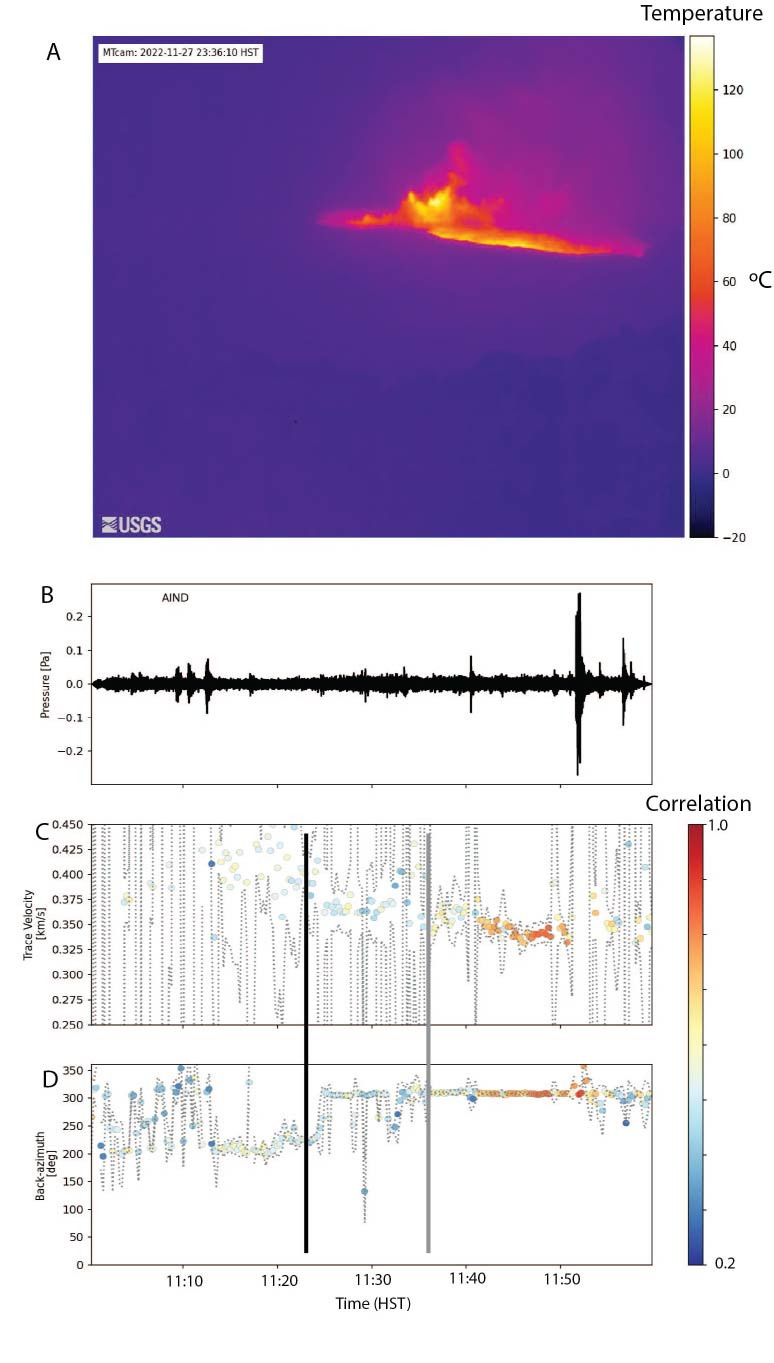

(ABOVE IMAGE) USGS: “Panel A is a thermal image showing first observation of strong ‘lava glowing’ at Mauna Loa, time-stamped 11:36 p.m. HST on November 27, 2022. An example waveform from the array of sensors at the ‘Āinapō (AIND) field station is shown in panel B. Coherency plots of wave velocities are shown in panel C and the direction of the computed eruption source compass direction, relative to the ‘Āinapō array, is shown in panel D. The colored dots in panels C and D represent incoherent signals (shown in light and dark blue) and coherent signals (shown in red, orange and yellow). Times for panel B, C and D are expressed in Hawaii Standard Time (HST). The black vertical line in panels C and D marks the early onset of the eruption at 11:23 p.m. HST. The grey vertical line shows the time when the thermal image in panel A was taken. Both of the vertical lines mark times before changes in the acoustic processing because it takes about 2 minutes for sound to travel from the eruption vent to the ‘Āinapō array.”

The global volcano monitoring community routinely installs clusters of acoustic sensors (called arrays) on the flanks of volcanoes that can measure both the audible noise (sounds we can hear) and the inaudible noise which have frequencies that human ears can’t sense (infrasound). Computer processing is then used to look for signals that come from a distinct direction, similar to the way humans train their ears and brains to determine where sounds come from.

HVO currently monitors our volcanoes using rapidly processed ‘near real-time’ data from acoustic arrays which measure pressure changes around our most active volcanoes, Kīlauea and Mauna Loa (figure panel B). The grouped sensor arrays are deployed in the field to allow computers to look for correlations in acoustic energy from Hawaii’s likely eruption centers.

The processing compares all waveforms of the array and looks at consistency (called coherency) of the waves under a range of conditions. In the plots (figure panels C and D) strong waveform coherency are marked by red and orange dots and incoherent waves are marked by light and dark blue. As an analogy, incoherent sounds are like the sounds you hear in the middle of a forest on a windy day and more coherent sound would be from a car honking on the road.

Coherent acoustic signals often have characteristics that allow them to be distinguished by the processing of array data, and two good indicators of coherency come from the wave speed and wave direction across the array. For example, near the surface of the Earth the sounds usually travel at speeds of about 0.3-0.4 km/s (~300-400 yards per second) (figure panel C). HVO’s ‘Āinapō infrasound array is located in the Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park and has a compass direction of about 300 degrees (figure panel D) pointing back to Mauna Loa summit. Automated detection can use these characteristics (coherency, wave speed and direction) to improve our ability to rapidly understand when an eruption is occurring at Mauna Loa summit.

Panel D of the figure shows that the compass back direction becomes very stable at about 11:25 p.m. HST which indicates that mild eruptive activity had started. Its timing was probably approximately two minutes earlier, at about 11:23 p.m. HST, given that it takes about 2 minutes for sound to travel from the summit of Mauna Loa to the ‘Āinapō array (shown as a black vertical line in figure panels C and D.) Indeed, panel A of the figure shows that by 11:36 p.m. HST, lava flows being generated by the new eruption were rapidly expanding across Mokuʻāweoweo, Mauna Loa summit caldera (grey vertical line in C and D). The progression and expansion of the lava is followed by a strong intensification of that activity around 11:40 p.m. HST (C and D). This shows the value of using multiple lines of information to evaluate eruptive activity.

In addition to acoustic methods, staff at HVO utilize a full range of volcano monitoring methods including seismic, deformation, gas, and webcam imagery. The data collected improve our situational awareness; evaluating the different datasets together can help scientists to understand the volcanic processes happening at any one time. This, in turn, helps HVO to keep the public well-informed about our active volcanoes.

by Big Island Video News11:51 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Scientists write about using sound to discern the exact time that the 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa began.