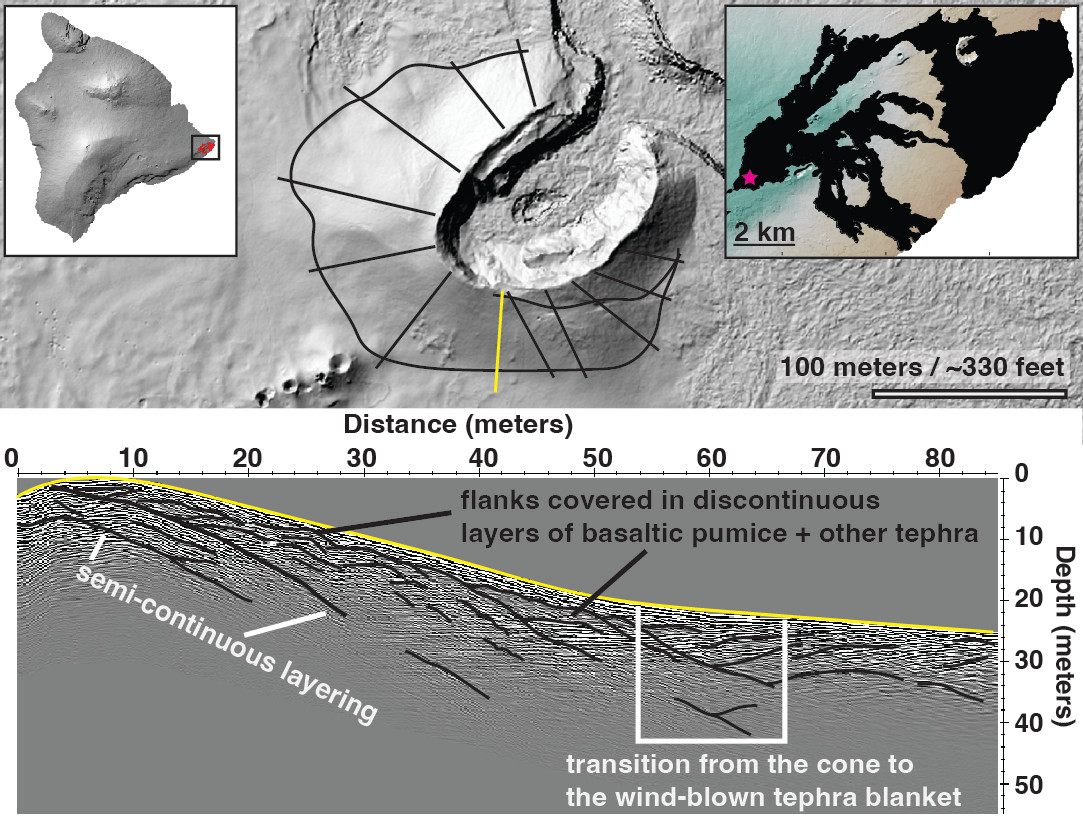

USGS: “The top panel shows a shaded relief map of Ahuʻailāʻau and the locations of the survey lines in black, with the radar line below highlighted in yellow. The lower panel shows an annotated radargram, noting where the GPR saw reflective boundaries in thicker black lines. These boundaries indicate layers of basaltic pumice and other tephra that are variably continuous and inconsistently thick.”

(BIVN) – This week’s Volcano Watch article courtesy U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates focuses on the now quiet volcano vent, Ahuʻailāʻau.

From this week’s article, written by National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellow Lis Gallant:

In the last few months, “Volcano Watch” articles have introduced several research projects funded by the Additional Supplemental Disaster Relief Act of 2019 (H.R. 2157). Each of these projects will help scientists better understand how Kīlauea volcano works and how the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption and collapse of Kīlauea summit happened.

Scientists from the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) and collaborators from the University of South Florida had the unique opportunity to get a peek at the layers inside Ahuʻailāʻau (the cone that formed around fissure 8) with ground penetrating radar (GPR) over the summer.

GPR is a technique that uses small radar pulses to detect objects and changes beneath the ground. When these pulses are transmitted into the ground, they encounter things like faults or the boundary between different lava layers. They hit these obstacles and reflect back towards the surface, where they are captured by a receiving antenna. Unlike medical X-rays, GPR uses low-frequency radio waves no more powerful or harmful than those picked up by household radios. Essentially, GPR allows us to “see” inside of the cone in a way that does not damage it in the long-term.

The transmitter and receiver are attached to a sled and guided along the ground surface and the data are collected in lines. We use different line directions and orientations to tie the lines together so we can get an idea of the layers beneath the surface in 3D.

You may be wondering how deep into the cone we are able to see, and the answer to that question depends on two main things. The first is the wavelength of the energy we transmit with the GPR—the longer the wavelength, the larger the antennae size, and the deeper we can see. The second is the type of ground we run the survey on—very wet clays and soils generally make for poorer survey conditions, whereas dry and hard layers are better. Luckily, things like lava and tephra make for excellent survey conditions!

We were able to image 50 feet (15 meters) into the cone for the Ahuʻailāʻau GPR survey using 100 megahertz (MHz) antennas. The data collected from GPR surveys are plotted on a “radargram.” Radargrams may look like modern art prints, but to the trained eye of a geophysicist these plots tell us a great deal about what is lurking beneath the surface.

The main purpose of this GPR survey was to help HVO scientists better understand how cinder cones grow. The name “cinder cone” is a bit of a misnomer because features like Ahuʻailāʻau are not built entirely out of uniform piles of cinders. In fact, Ahuʻailāʻau is mostly basaltic pumice!

Most cartoon drawings of cinder cones illustrate their insides like a multi-layered cake that slopes down and outwards from a central high point. Some of these layers are made of cinders (the cake), while others can be bits of lava that were still molten when they landed on the sides of the cone (the icing). As things like the fountain height and the wind direction change, so too do the thickness and location of the eruptive deposits.

The pictured radargram shows that things are a little more complicated and not nearly as delicious as the simple sloped cake model. The upper part of the cone in this area is made mostly of tephra (fragments of lava that travel through the air before being deposited on the ground). These layers are variably thick and are not continuous down the flank of the cone. There is little spatter—globs of lava that stick together when they land—present, as well.

Essentially, we have a very lumpy cake that lacks well defined layers and contains only a small amount of icing. The sections of the cone that bound the opening into the spillway contain a greater amount of spatter than the section shown in the radargram.

Combining our survey results with monitoring data and other geophysical surveys allows us to understand how this prominent feature formed during the three-month-long eruption of Kīlauea’s lower East Rift Zone in 2018. We plan to share the results of this Ahuʻailāʻau survey after we complete the data processing.

by Big Island Video News11:17 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

PUNA, Hawaiʻi - Scientists are taking a look at the layers inside the volcanic cone that formed in 2018 around fissure 8 using ground penetrating radar.