USGS: “An HVO scientist aims the ‘field FTIR’ at spattering lava from the current eruption in Halema‘uma‘u crater, at Kīlauea summit, on October 4, 2021.” (USGS photo by P. Nadeau)

(BIVN) – As the summit eruption of Kīlauea Volcano continues with an off-and-on pattern of activity – the eruption was once again paused as of the morning of Sunday, December 26 – the latest Volcano Watch article focuses on gas measurements.

A sulfur dioxide (SO2) emission rate of approximately 5,300 tonnes per day was measured on December 24, when eruptive activity was more vigorous before the pause, the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory reported on Sunday.

In its weekly Volcano Watch article, HVO scientists and affiliates wrote:

Most people in Hawai‘i know about sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas, the major component of vog. But, have you ever found yourself wanting to know the SO2/HCl (sulfur dioxide/hydrogen chloride) ratio in volcanic gas? Or the amount of CO2 (carbon dioxide) dissolved in volcanic glass?

If you’re not a volcanologist or geologist, probably not. But at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), we do need to know those things. Magma contains dissolved gases, or volatiles, which drive eruptions. And while gases in the air and dissolved volatiles in molten magma (preserved as glass and glass inclusions in minerals) may not seem like they’d be measured the same way, we can use the same principles and techniques to measure both and help us understand eruptive activity.

To make each of those types of volatile measurements, we use an instrument called a Fourier Transform Infrared spectrometer, or FTIR. FTIR instruments detect incoming infrared (IR) radiation—the type of radiation associated with hot/warm objects, having wavelengths slightly longer than the visible light we can see with our eyes.

But how can we tell which gases are there?

It turns out that gases absorb radiation, and each gas—like CO2, HCl, SO2, H2O (water vapor), and others—has its own unique signature of how much it absorbs at different wavelengths.

One slightly different, but common, example of an absorbing gas that many people know about is ozone (O3). Ozone in the atmosphere protects us from some of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation (shorter wavelengths than visible light) by absorbing UV wavelengths very strongly. SO2 also absorbs strongly in the UV range; HVO uses UV to measure SO2 emission rates.

However, many important volcanic volatiles don’t absorb UV very well, but they do absorb strongly in the IR range. So, we turn to FTIR to measure them. Or, more precisely, one of our two FTIRs! Yes, HVO has two different types of FTIR, which we use for different applications.

For measuring gases in air, we take our ‘field FTIR’ and head out to where the volcanic plume is. We need a source of IR energy and, luckily, lava is a great source of IR because it’s so hot! So, when we have an eruption, we can aim the FTIR at hot, glowing lava. If there’s no lava around, we can still measure the gas by aiming the FTIR at a special lamp that generates IR.

Once we have the IR source, we need to position the FTIR so the volcanic gas is between the IR source and the FTIR. The FTIR measures relative amounts of IR radiation at different wavelengths, some of which is absorbed by the volcanic gases. We then process the data and calculate important gas ratios, like CO2/SO2 and SO2/HCl, which can give us information about how magma and volatiles are transported in the volcanic plumbing system.

But what about the other FTIR?

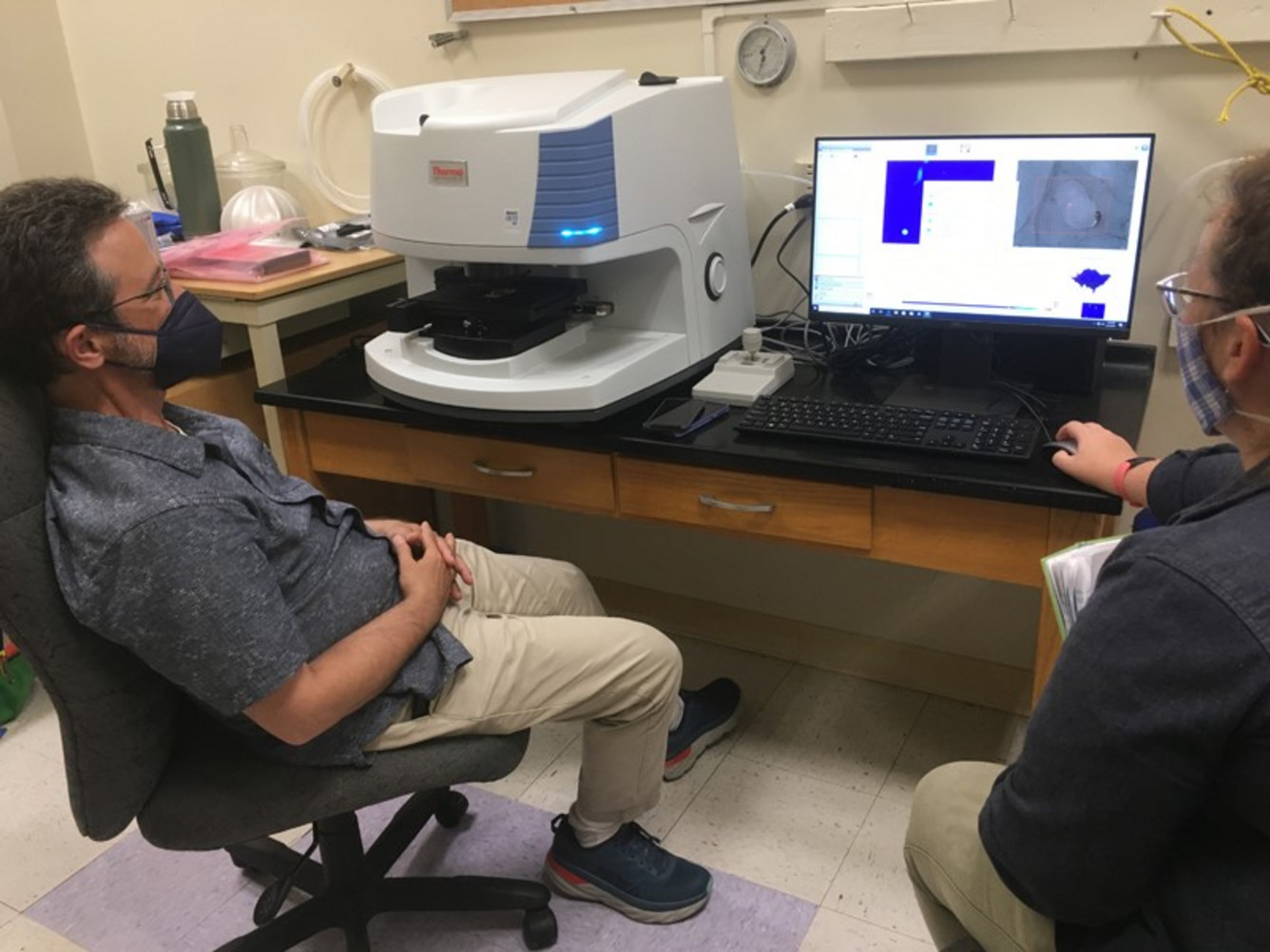

USGS: “Two USGS scientists measure H2O and CO2 dissolved in tiny chips of volcanic glass using the ‘lab FTIR’, currently housed at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo (UHH), until new, permanent HVO facilities can be built.” (Photo courtesy of D. Bevens (UHH), taken on August 24, 2021)

That would be our ‘lab FTIR,’ which doesn’t venture out near the volcanic plume like the ‘field FTIR’ does. Instead, the ‘lab FTIR’ is used for measuring small amounts of H2O and CO2 dissolved in minerals and volcanic glass.

The principles are the same—the lab FTIR has an IR source and a radiation detector that measures IR intensity at many different wavelengths. But instead of a volcanic plume passing between them, we insert a tiny, carefully polished chip of mineral or glass into the path between the IR source and the detector.

Minerals and glasses—especially those that erupt out of gas-rich volcanoes—often have CO2 and H2O still dissolved in them, which will absorb IR at those characteristic wavelengths just like volcanic gases in the air. As long as we know how thick the tiny chip of glass or mineral is, the FTIR can then tell us how much of those gases are dissolved in those little solid pieces. Once we know that, we can determine things like how deep that erupted material came from and how quickly it erupted.

Even if Santa doesn’t bring you an FTIR this year, don’t worry—HVO has two, and we will keep using them to learn more about the volcanoes here in Hawaii, their eruptions, and the gases that drive them.

by Big Island Video News9:02 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - The USGS describes how the use of an instrument called a Fourier Transform Infrared spectrometer, or FTIR, is used to measure volcanic emissions.