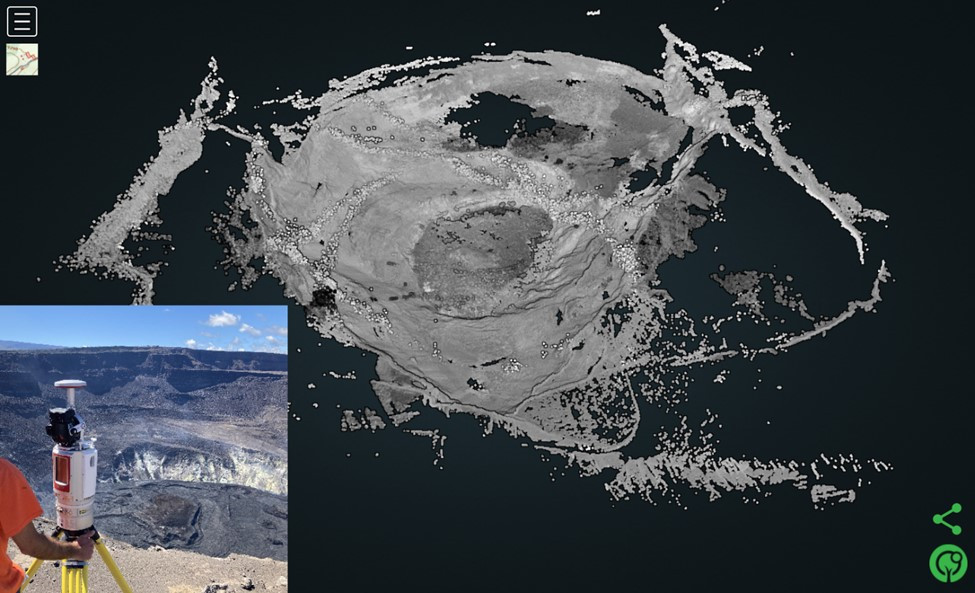

USGS: “Main frame: A composite of the point clouds resulting from HVO’s terrestrial laser scanning surveys of Halemaʻumaʻu crater since January 2021, viewed from the southwest. The central region of the crater, including the lava lake, is reliably captured in all surveys. Further afield the point clouds become sparser, as the laser reflections from such distances and angles escape detection by the instrument. Inset frame: The terrestrial laser scanning instrument rotates through a scan on the south rim of Halemaʻumaʻu on June 10, 2021.”

(BIVN) – The eruption at the summit of Kīlauea volcano continues, and scientists are using various tools to track the ongoing activity.

UPDATE – (Dec. 4) – The USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory says that as of Saturday morning, December 4, “the rate of eruption has decreased sharply but nonetheless all lava activity is confined within Halemaʻumaʻu crater in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. Volcanic gas emission rates remain elevated.”

In this week’s Volcano Watch article, USGS HVO scientists and affiliates write about the “cloud of ten thousand points”:

Scientists at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) largely rely on aerial data collection for making maps of ongoing eruptions at Kīlauea. Most commonly, scientists collect a series of overlapping aerial photos (optical or thermal).

A technique called structure-from-motion is then uses motion parallax to construct a two-dimensional map or three-dimensional model of the area by matching the same features across multiple images.

HVO’s aerial photography is typically done during helicopter overflights, which are limited by budget, weather, and aircraft availability. Since 2018, small unoccupied aircraft systems (sUAS, or “drones”) have augmented the helicopter overflights to some degree, but they have their own limitations as well. While both of these techniques are excellent for making maps and topographic models, understanding some processes requires even more detailed surveys conducted from the ground.

The modern workhorse for ground surveying is terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) using light detection and raging (LiDAR) instruments. LiDAR may sound familiar to longtime “Volcano Watch” readers, because the basic technique was described in a November 2020 article that discussed an aerial LiDAR survey at Kīlauea. TLS surveys are similar, with a ground-based instrument emitting laser pulses and measuring their return times after reflecting off topographic features.

TLS surveys work best when there is a substantial amount of topographic relief, providing the instrument with good line-of-sight views of distant features. The current lava lake provides an ideal situation because scanning can be done from the crater rim, looking down on the eruptive features. Both the December 2020–May 2021 and September 2021–present eruptions in Halemaʻumaʻu crater have been surveyed using TLS LiDAR.

HVO does not have a TLS LiDAR instrument of its own to survey the growing lava lake, so some colleagues have lent a helping hand. The team at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) — who had previously collaborated on a TLS study of the 2008-2018 Halemaʻumaʻu lava lake — loaned HVO a TLS LiDAR instrument shortly after the onset of the eruption in December 2020.

CRREL’s LiDAR instrument is a Class 1 laser product, meaning that the laser pulses are safe for the eyes of bystanders and any nearby wildlife (some higher-power instruments require safeguards). For each scan, the LiDAR instrument is set up on survey tripod to rotate through 360 degrees over the course of approximately 15 minutes. These scans produce “point clouds,” which are digital collections of reflection points in three-dimensional space, depicting topographic features.

HVO scientists have completed eight TLS surveys of Halemaʻumaʻu since January. Most of these surveys involve visits to the west and south rims of the crater, for at least one scan from each direction. On two occasions, the instrument has been taken to the edge of the eastern down-dropped block within the 2018 collapse crater, for scans at closer range to the lava lake.

The point clouds from HVO’s TLS surveys at Halemaʻumaʻu have allowed scientists to build high-resolution digital elevation models of the crater and lava lake. The unmatched accuracy can record detailed topography as small as 5 millimeters (0.2 inches), from a distance up to 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) away. In comparison, most aerial photography from HVO helicopter overflights will yield a resolution of approximately 1 meter (yard).

LiDAR also avoids misalignment errors that can warp structure-from-motion models and further decrease their accuracy. This is because LiDAR is a “direct” measurement technique, with the laser pulses actually reflecting back from the measured features. In fact, HVO uses the TLS LiDAR data to help calibrate the structure-from-motion datasets for the Halemaʻumaʻu eruptions, improving their accuracy.

HVO hopes to obtain its own TLS LiDAR instrument in the near future, which will open up even more research possibilities using this technology. But in the meantime, we sincerely thank the team at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory for their ongoing assistance in studying the eruptive activity at Kīlauea.

by Big Island Video News10:05 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - USGS HVO scientists have completed 8 terrestrial laser scanning surveys surveys of Halemaʻumaʻu since January.