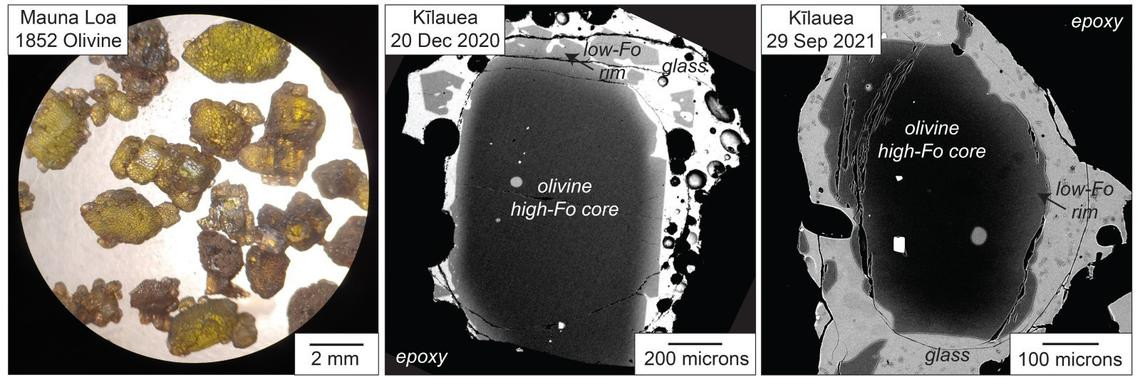

Images of olivine from Hawaiian volcanoes. USGS: “In olivine the abundance of magnesium (Mg) is expressed as the forsterite content (Fo)—which is a ratio of how much Mg there is compared to the iron (Fe). Left: Green olivine from Mauna Loa’s 1852 eruption, viewed under a microscope. USGS photo by K. Lynn. Middle: Zoomed in electron image of the inside of an olivine from Kīlauea’s December 2020 eruption, where grayscale indicates the relative abundance of iron (Fe). The darker core (black inside) of the olivine is higher in Mg (and a higher Fo content) than the lighter rim (gray outside). This crystal is approximately 800 microns (0.3 inches) across. Right: Another electron image of olivine from 29 September 2021 that also has changes in Fo content between the core and rim. This crystal is smaller, only 400 microns (0.15 inches) across. Images from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa electron microprobe.”

(BIVN) – The eruption of Kīlauea volcano continues, with all activity confined to Halemaʻumaʻu crater at the summit within Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park.

In this week’s Volcano Watch article, Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Research Geologist Kendra J. Lynn writes about the study of olivine crystals to better understand the events that led up to the current eruption. From Lynn:

Olivine crystals—the beautiful green mineral common in Hawaiian lavas – record when and where magmas move inside Hawaiian volcanoes before they erupt. We can actually use these little crystals like clocks to better understand the magmatic events leading to the December 2020 and September 2021 summit eruptions at Kīlauea.

Lavas and their minerals erupted from Hawaiian volcanoes provide clues to the history of the magmas that are eventually erupted. Kīlauea’s recent summit eruptions allow us “a glimpse inside” the volcano and the chance to learn more about where the magma erupted in Halema‘uma‘u crater came from and how quickly it moved to the surface.

Geologists measure the chemistry of the erupted materials – including rapidly cooled lava (glass), minerals, and dissolved gases or gas bubbles – to find out how hot the magma was, how long it sat inside the volcano prior to erupting at the surface, and how different magmas might have mixed (older and cooler versus fresher and hotter magma).

Olivine is primarily made of the elements magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe) along with silica. The ratio of Mg and Fe, also known as the forsterite (Fo) content, can tell us several things about the magma that the crystal grew in.

Higher Mg in olivine (and therefore higher Fo) means that crystals grew in hotter, and usually deeper, magmas. If the olivine Fo content is low, it tells us that crystals grew in a cooler, and usually shallower, magma.

After searching for olivine crystals in tephra (pumice, ash, and Pele’s hair) erupted by Kīlauea in December 2020 and September 2021, USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) scientists worked with the electron microprobe lab housed at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa to take pictures of the insides of the olivine crystals.

These images show that Kīlauea’s recently erupted olivine can be zoned, meaning that the cores (or insides of the crystals) have different Fo than their rims (the exterior edges of the crystals). These examples show what we call normal zoning – where Fo decreases from the inside of the crystal to the outside.

Normal zoning in these crystals tells us that they first grew in a deeper, hotter part of Kīlauea and then the rims of the crystals grew later after the magma had moved to a shallower, cooler region.

The presence of zoned crystals is rather exciting for Kīlauea’s summit – olivine from the lava lake that was active from 2008–2018, prior to the 2018 summit collapse, were typically homogeneous, meaning that they didn’t have any zoning.

These changes in olivine Fo are also special because they actually record time through a process called diffusion. Think about putting your cold hands on a warm mug of tea or coffee. Thermal diffusion allows the heat from the mug to move into and warm your hands.

In the same general process, Mg atoms from the olivine core can diffuse toward its rim over time while the olivine sits in a hot magma. By measuring the change in Fo from core to rim, and then applying a model of this change, we can calculate how long crystals sat at the shallower level where the rims grew before they erupted.

Kīlauea’s 2020 olivine crystals have modeled diffusion times of about 60 days or less. This suggests that the crystals, which originally grew deeper in the volcano, moved up to shallow regions (a few km or less than a couple miles below the ground surface) about 60 days before they erupted.

Around 60 days before Kīlauea’s December 2020 eruption, in late October, HVO detected the first set of earthquake swarms during the period of unrest leading to the eruption. Though the initial earthquake swarm occurred under Nāmakanipaio Campground, the modeled olivine crystal diffusion times suggest that the earthquakes could have been a sign that magma was intruding shallowly under Kīlauea’s summit.

In the next few weeks, olivine crystals from Kīlauea’s eruption that began on September 29 will be measured on the USGS California Volcano Observatory’s electron microprobe. The data will then be modeled to calculate the timescales from these most recent “crystal clocks,” letting us know if the same process was repeated this Fall or if something new and different happened prior to the most recent eruption of Kīlauea.

by Big Island Video News9:19 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Scientists are using olivine crystals to better understand the events that led to the current eruption at the summit.