(BIVN) – One week ago, a wildfire ignited near Mana Road on the dry side of Hawaiʻi island. Winds spread the fire fast, and soon residents of Puʻukapu Homestead, Waikiʻi Ranch, and Waikoloa Village were forced to evacuate their neighborhoods for fear their homes would be lost to the blaze.

Assisting emergency responders was a “spaceborne sentinel” familiar to geologists and meteorologists who monitor conditions on Hawaiʻi island. It is the subject of this week’s Volcano Watch article by USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates:

Geologists at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) had their mobile phones buzzing this past week with automated alert messages, notifying them that there was something new and hot on the Island of Hawaiʻi. Although the internal alert system is meant to detect new volcanic activity, no eruption was occurring.

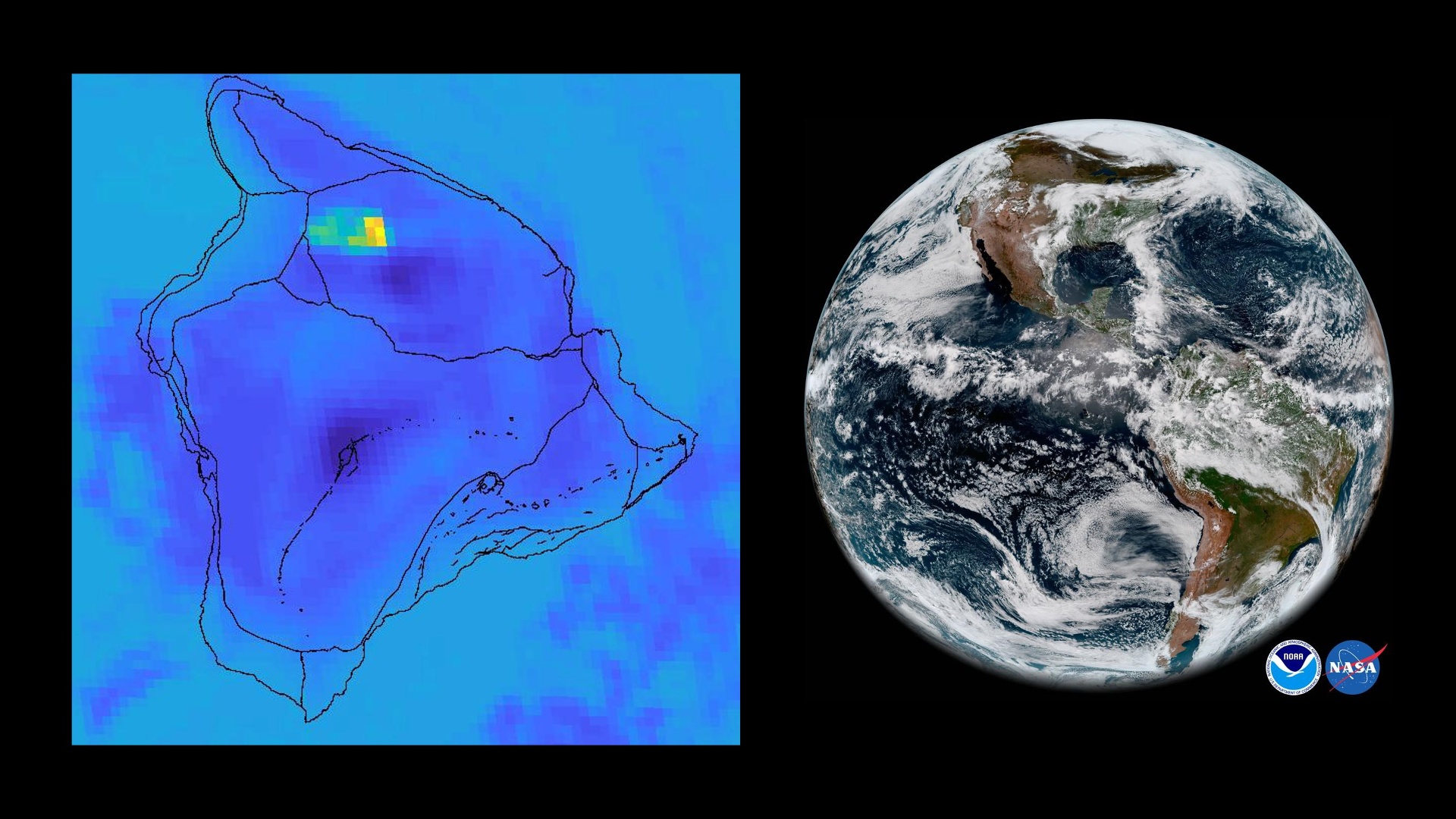

Instead, the alert was triggered by an image of the recent large brush fire on the west side of Mauna Kea. The image that captured this activity doesn’t just cover the Island of Hawaiʻi – it encompasses much of the Pacific region.

What could possibly have such a broad view of the Earth? The answer: a geostationary satellite, orbiting 22,000 miles (35,000 km) above Earth’s surface.

The image originated from a Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES-17), operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). GOES-17, launched in 2018, is a relatively new edition in a series of GOES satellites that date back to 1975, when GOES-1 launched.

Many imaging satellites are polar orbiting, staying closer to Earth’s surface in a low orbit. They image the Earth like you might mow a lawn—in narrow, sequential strips as the satellite traverses from pole to pole.

Geostationary satellites like GOES, however, have orbits that hover over a single spot on the Earth. This requires being much farther from Earth than polar orbits, but it has the benefit that the satellite can “see” the entire side of the planet in one view.

The United States uses two GOES satellites to cover the whole country. GOES-16 (also called GOES-East) hovers over longitude 75° West (near the east coast), viewing the mainland and much of the Atlantic Ocean. GOES-17 (GOES-West) is over longitude 137° West (close to halfway between Hawaii and the mainland) and views the western U.S. and much of the Pacific Ocean.

The primary mission of GOES satellites isn’t to detect volcanic activity or forest fires, but to keep a constant watch over the weather. The broad view allows scientists to track weather systems as they evolve and migrate, providing critical data for forecasts.

Weather monitoring uses wavelengths of visible and infrared light to characterize the atmosphere. Fortunately, the satellite infrared channels can also pick up hot thermal signals on the ground, such as those from fires and eruptions.

The geostationary nature of GOES-17 allows it to image areas rapidly—every 5–15 minutes —providing a timely view of what’s happening on this side of the planet. The satellite also has a mode to image smaller areas of Earth’s surface at even higher rates (every 30 seconds), by request in special cases, such as during a volcanic eruption or large fires. Polar-orbiting satellites, on the other hand, might only cover a given spot on the Earth twice a day.

The drawback of the distant geostationary orbit of GOES, however, is that the resolution of the images is generally lower than that of polar-orbiting satellites. The infrared channels on GOES-17 have a resolution of 2 km (1.2 miles), an improvement over its predecessor, GOES-15, which had a resolution of 4 km (2.5 miles).

The lower resolution means that GOES images aren’t adequate to map out the precise outline of a lava flow, or locate the exact location of a vent. However, the high image frequency provided by GOES is ideal for detecting the onset of new volcanic activity on the surface, while giving a general idea of where that activity is located (for example, a volcano’s summit region, or lower rift zone).

Think of GOES as a warning bell to mobilize the forces, adding to the suite of other monitoring tools used by volcano observatories to detect eruptions. While seismic and ground-deformation networks are sensitive to changes below the surface, the GOES satellite is a tool for spotting new lava reaching the surface.

The GOES satellite acts as a high-tech sentinel, maintaining an unwavering watch for eruptive activity, not only in Hawaii, but across the U.S.

GOES images and raw data are all publicly available online, just minutes after acquisition. One online interface is provided by NOAA.

HVO is still refining its alarming and use of GOES data, with the hope that it will help in the next eruption onset. With a history that “goes” back to 1975, it’s likely that GOES satellites will remain on watch duty for many years to come.

by Big Island Video News7:17 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI ISLAND - This week's article focuses on the GOES-17 geostationary satellite, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.