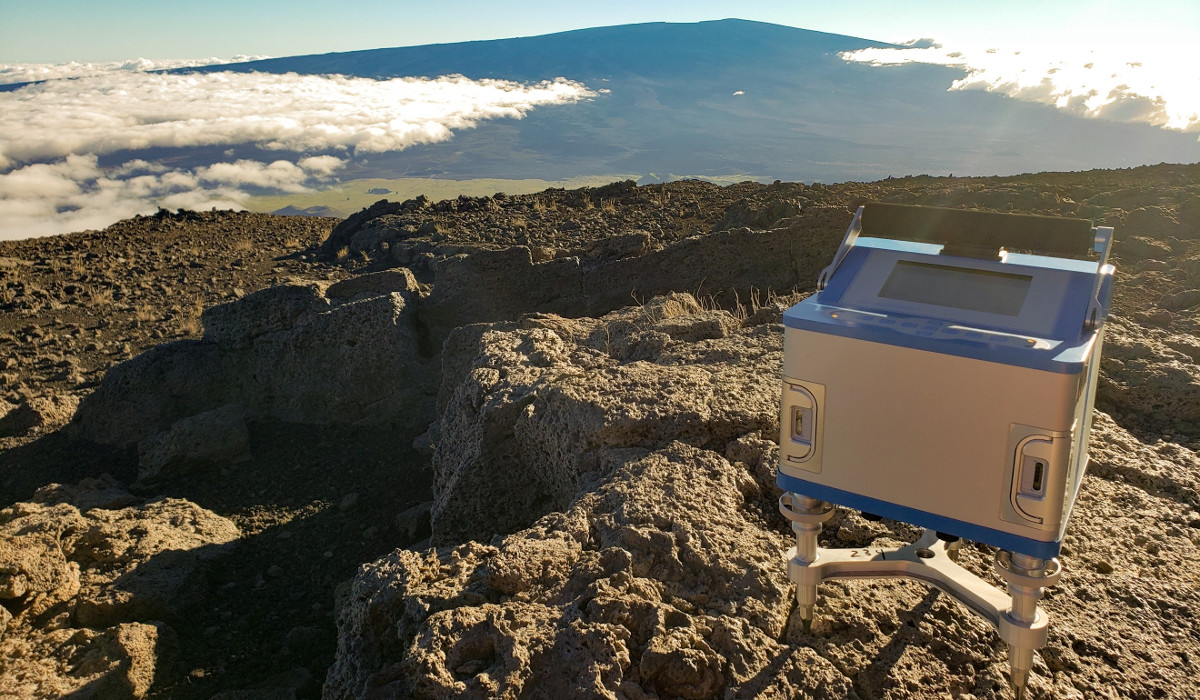

USGS image, captured on April 24, from a research camera positioned in the observation tower at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. The camera looks northwest toward the summit and Northeast Rift Zone of Mauna Loa.

(BIVN) – Mauna Loa is not erupting and remains at Volcano Alert Level ADVISORY. This past week, about 175 small-magnitude earthquakes were recorded below the giant Hawaiʻi island volcano, and an earthquake swarm occurred southwest of the summit on April 16th-17th.

The U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory says that while Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements continued “to show a slightly extensional summit deformation pattern” this week, other monitoring data streams “show no significant change in deformation rates or patterns that would indicate increased volcanic hazard at this time.”

Gravity measurements are among the data stream being monitored. From this week’s Volcano Watch article written by USGS HVO scientists and affiliates:

Gravimeters, essentially extremely precise pendulums, can measure a change in the force of gravity to one-in-one billionth of the force you feel every day. This force varies based on the distance and the amount of mass between the instrument (or you) and the center of the Earth.

It’s 5 a.m. and a somewhat sleepy scientist is getting ready to leave his home in Honomū and head to the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) office on Kamehameha Avenue in Hilo. Yawning—and not quite fully caffeinated—he says goodbye to the dog following him around the kitchen who’s wondering why they’re up so early.

At the HVO office, he picks up two identical instruments the size of a shoebox—gravimeters—and loads them into a USGS four-wheel-drive vehicle. Today will be a long day driving from Hilo to the summit of Mauna Kea and back—twice.

But these days are necessary, and any day spent on the mountain is a good day, especially if the sky is clear and views stretch to the horizon. Between Hilo and the summit of Mauna Kea, the HVO scientist will stop approximately half a dozen times at a series of locations (benchmarks) established beginning in the 1960s. At these benchmarks, the two gravimeters will be used to measure the variation of the force in gravity.

Days like this one are not particularly eventful; they consist of driving from one measurement site to another and waiting for the gravimeters to stabilize at each new site. They’re filled with audiobooks, Hawaii Public Radio, and listening to the sounds of the wind. These are not the exciting days trekking on the floor of Kīlauea caldera or flying by helicopter to the summit of Mauna Loa.

Gravimeters, essentially extremely precise pendulums, can measure a change in the force of gravity to one-in-one billionth of the force you feel every day. This force varies based on the distance and the amount of mass between the instrument (or you) and the center of the Earth.

Just like atmospheric pressure, the force of gravity changes depending on your altitude. For example, the higher in elevation you go (like driving up a mountain), the farther away you are from the center of the Earth (and its mass), and the weaker the force of gravity. This elevation effect is the primary contribution to changes in gravity measured on Mauna Kea. The changes in gravity are not as noticeable as the change in the atmosphere (it’s hard to breathe at the summit), but the average person also weighs about one-third of a pound less—equivalent to the weight of an orange—at the summit of Mauna Kea than they do in Hilo!

Since the 1970s, small changes in time-varying gravity (microgravity) have been measured on the active volcanoes Mauna Loa and Kīlauea to determine whether magma is accumulating in their magma reservoirs. This intruding magma often opens and fills cracks and/or empty spaces, causing a net increase in the volcano’s mass that can be measured with a gravimeter. Measuring the gravity is an independent way to confirm whether ongoing uplift, like that occurring at Mauna Loa since 2014, is from new magma intruding into the volcano.

The precision and sensitivity of the gravimeters make them extremely delicate, and they require regular calibration. As the dominant effect we measure is from changes in elevation, our ability to measure volcanic changes on the high elevations of Mauna Loa (13,680 ft or 4,170 m) requires us to calibrate the instruments over similar elevations on Mauna Kea where there is currently no influence from volcanic activity (the last eruption was more than 4,500 years ago). Without Mauna Kea, we would have to send the gravimeters back to California to be calibrated, making them susceptible to damage on their long journey.

The opportunity to calibrate HVO gravimeters on Mauna Kea provides the ability to design a gravity monitoring program to help understand volcanic unrest at Mauna Loa. Along with ground deformation and seismicity, future gravity surveys could help detect how much magma is slowly being supplied to Mauna Loa’s shallow magma storage system. On the Island of Hawaiʻi, Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa have played important roles in the past; today, they are acting together to help inform us about future volcanic activity.

by Big Island Video News7:42 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Measuring gravity is an independent way to confirm whether ongoing uplift is from new magma intruding into the volcano.