(BIVN) – From this week’s Volcano Watch article written by Julie Chang, a geologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory:

A new project at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) is once again making use of old aerial photographs and field notes that were used to make geologic and hazard maps. Buried within hundreds of old mapping photos and field notes are the locations and thicknesses of several ash deposits on the flanks of Mauna Loa that have never been fully quantified.

Ash deposits are a product of explosive volcanic eruptions that have periodically dominated past eruptive activity. The largest explosive eruptions deposited thick ash layers that covered wide areas of Kīlauea and Mauna Loa volcanoes. Knowing the locations and thicknesses of related ash deposits allows us to better characterize the explosive nature of these eruptions.

Aerial photographs of the Earth’s surface can be taken from any type of aircraft, including satellites, airplanes, helicopters, or Unoccupied Aircraft Systems (UAS). In traditional aerial photography, a large-format camera is mounted under a fixed-wing airplane that flies in rows of straight lines, capturing sequential overlapping photos of the area below it.

Air photo perspectives can be oblique or vertical, depending on their intended use. Many air photos are used to create orthophotos, which are vertical air photos that have been corrected to remove distortion from camera tilt, lens aberrations, and topographic relief. Both orthophoto and topographic maps can be made from aerial photos and allow true distances and angles to be measured.

The USGS mapping group began acquiring air photos for mapping in the 1930s in conjunction with the military and US Department of Agriculture (USDA). At least one air photo survey was done per decade between the 1950s and 1970s for each of the Hawaiian Islands. Over the Island of Hawaiʻi, for example, photographic surveys were flown in 1954 (USGS HAI), 1961 (USGS VXJ), 1964–1965 (USDA EKL), and 1976–1978 (USGS VEEC).

Digital copies of black and white aerial photographs for the Hawaiian Islands can be accessed through the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa: Maps, Aerial Photographs, and GIS (MAGIS) website. The website provides an image viewer with flight lines taken during the surveys and the location of each air photo.

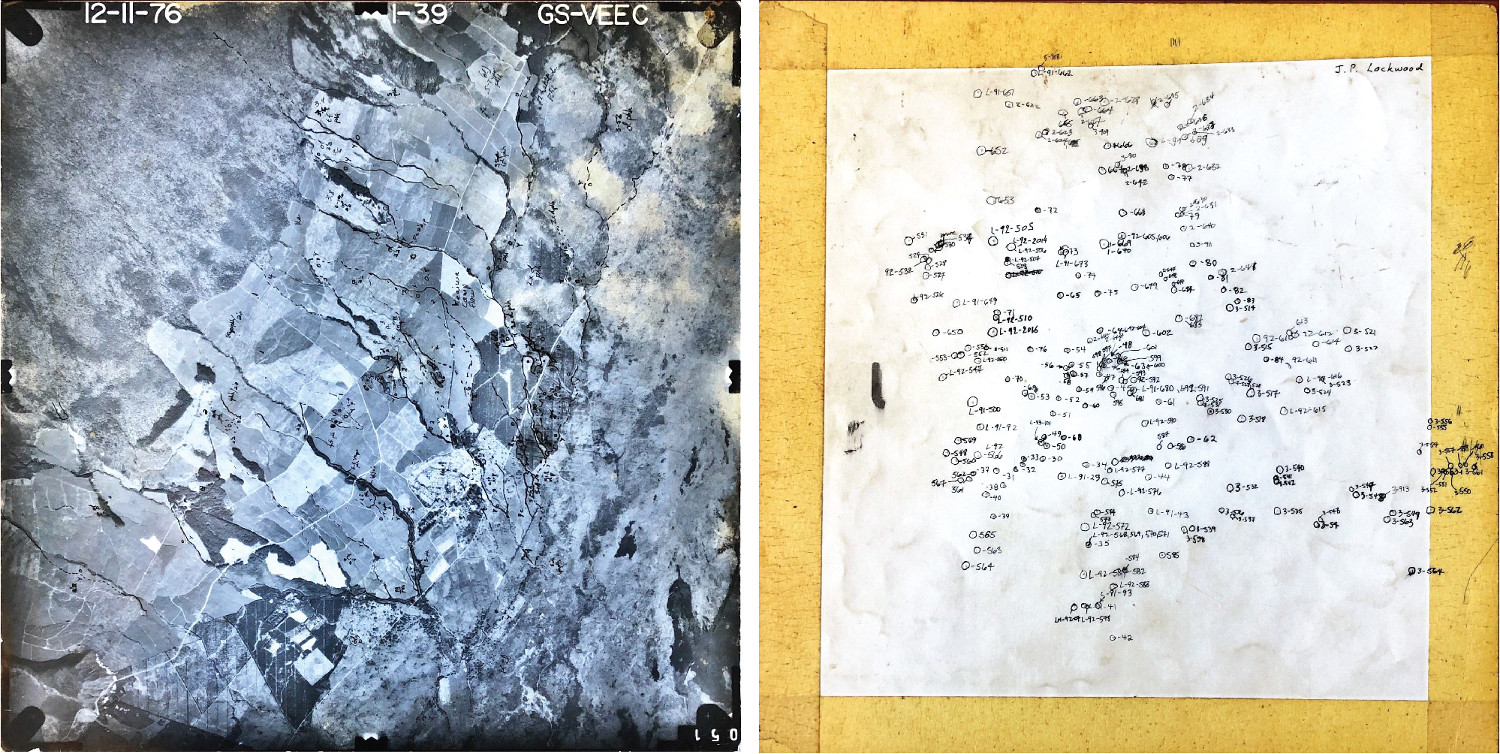

HVO geologists used air photos as the primary way to map geologic features and locate their position in the field prior to the widespread availability of GPS. They used landmarks (roads, trees, buildings, faults, streams) to find where they were in the field, and then they put a pin hole through the air photo and labeled the back with a site number. They recorded the site number in their field notebook, along with the geologic observations made at that locality. Interestingly, this is still a useful skill when you can’t get a good GPS location.

Compiling decades-worth of aerial photos and field notes into digital form is a Herculean task. So far, more than a thousand ash locations around the Island of Hawaiʻi, primarily on Mauna Loa, have been compiled. Of these, about 230 stratigraphic sections containing ash have been constructed, based on information from old field notes and constrained by the ages of lava flows that have been dated.

Dating charcoal found within ash deposits and adjacent lava flows helps constrain how often explosive eruptions occur. See the Volcano Watch article from October 22, 2020, “Charcoal, a game changer for understanding processes in young volcanic terranes.”

Ash deposits on the flanks of Mauna Loa span ages as young as 380 years BP to older than 31,000 years BP. Ash thickness ranges from about 3 cm (1 in) to more than 10 m (33 ft). However, much more work needs to be done to determine how frequent explosive eruptions are and how many individual explosive events these ash layers represent.

The new information extracted from these old air photos and from revisiting these sites will contribute to a better understanding of future explosive eruptions on the Island of Hawaiʻi. The ash horizons contain critical information about eruptions including how big they can get, where their sources are, and how often they occur. The goal is to build better assessments of the hazards of explosive eruptions and how they may affect the communities that are currently living on the flanks of Hawaiʻi’s most active volcanoes.

by Big Island Video News7:51 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI ISLAND - The USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory is looking back on old aerial photographs and field notes to move forward.