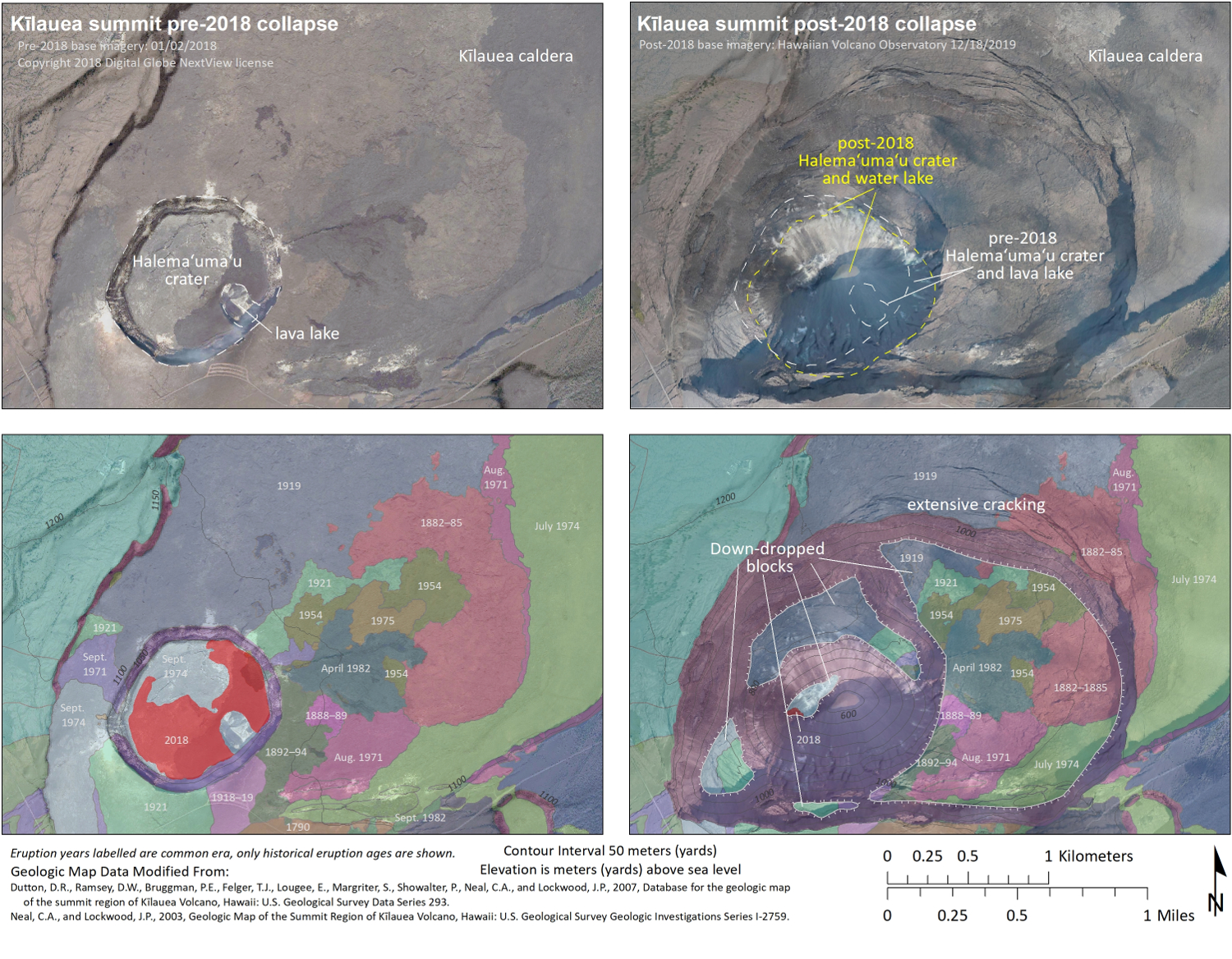

A comparison of aerial imagery and geologic deposits before and after Kīlauea’s 2018 summit collapse. Large cracks are visible in lava flow deposits on Kīlauea caldera floor above the areas that down-dropped during the summit collapse-events of 2018. USGS maps.

(BIVN) – This week’s Volcano Watch article, written by U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates, focuses on the dramatic changes at the summit of Kīlauea volcano following the 2018 eruption. The USGS HVO wrote:

Kīlauea’s 2018 summit collapse dramatically transformed the geometry and appearance of Halema‘uma‘u crater and Kīlauea caldera. Last week’s “Volcano Watch” article described how the 2018 events impacted the magma plumbing system beneath the surface of Kīlauea’s summit. This week, we’ll explore how the 2018 events impacted the geologic deposits on the surface.

Kīlauea’s summit is no stranger to change. Several summit drainages or collapses in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are documented in early western accounts. Reverend William Ellis, author of the first written description of Kīlauea, observed of the summit in 1823, “…that the crater had been recently filled with liquid lava…and had, by some subterranean canal, emptied itself into the sea, or inundated the low land on the shore.”

Ellis’ description hypothesizes that Kīlauea’s summit had been erupting before a flank eruption drained the summit. Indeed, an eruption of Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift Zone in 1823 may have contributed to the summit collapse that Ellis described, much like Kīlauea’s summit collapse in 2018 was accompanied by the lower East Rift Zone eruption.

Kīlauea’s summit was partially drained, sometimes leading to enlargement of Halema‘uma‘u or collapse of portions of the caldera floor, in 1823, 1832, 1840, 1868, 1886, 1891, 1894, 1916, 1919, 1922, 1924, and 2018. It’s unclear why Kīlauea summit collapses were less frequent in the past century, but perhaps prolonged flank eruptions on Kīlauea’s middle East Rift Zone (Mauna Ulu 1969–1974 and Pu‘u ‘Ō‘ō 1983–2018) played a part.

Some Kīlauea summit drainages or collapses were accompanied by lower-elevation flank eruptions; others, by likely “failed” eruptions, wherein magma intruded into the flank of the volcano but wasn’t erupted onto the surface.

In the past, Halema‘uma‘u crater was described as being transformed into a pit of “tumbled masses of rock blocks” after a drainage or collapse of Kīlauea summit. This description is certainly applicable to the current appearance of Halema‘uma‘u, with its steep crater walls and rubble base.

Nineteenth-century descriptions of Kīlauea summit after a collapse sometimes describe a “black ledge”—evidence of summit lava-lake activity—bordering collapsed areas. Though there was a summit lava lake before the 2018 collapse, it left no such “black ledge;” those deposits are now part of the rubble at the base of Halema‘uma‘u. The 2018 collapse almost completely erased the geologic evidence of Kīlauea’s 2008–2018 summit lava lake! How did the 2018 summit collapse impact other geologic deposits within Kīlauea caldera?

A comparison of pre- and post-2018 geologic maps shows that before 2018, the floor of Halema‘uma‘u crater consisted of lava flows erupted in 1974 and 1982 and overflows from the 2008–2018 summit lava lake. All of these deposits are now part of the rubble at the base of the current (post-2018) Halema‘uma‘u. Now, another type of lake (water) occupies the bottom of Halema‘uma‘u, although not in the same location as the 2008–2018 lava lake.

The 2018 Kīlauea summit collapse also impacted a broader area of Kīlauea caldera. Before 2018, Kīlauea caldera floor was a mosaic of different-aged lava flows—nineteenth century flows that inundated much of the caldera floor mostly overlain by more recent flows from summit eruptions in 1918–1919, 1919, 1921, 1954, 1971, 1974, 1975, and 1982.

During the many earthquakes that accompanied the collapse events of 2018, these deposits on the floor of Kīlauea caldera were jostled, cracked, and shifted. Portions of them were lowered over one hundred meters (yards) and likely shifted laterally several tens of meters (yards).

Fragments of these older lava flow deposits remain intact on the “down-dropped blocks” that formed within Kīlauea caldera during 2018. Lava flows from 1919 and 1974 are on the surface of the smaller down-dropped blocks, and numerous lava flows erupted over the past 150 years remain on the largest of the down-dropped blocks.

More detailed future geologic mapping will reveal how much these deposits were impacted by Kīlauea’s 2018 collapse. A previous “Volcano Watch” article describes the new outcrops exposed in the fault scarps formed during 2018 and their importance to better understanding Kīlauea’s eruptive history.

Changes to Kīlauea’s summit as a result of the 2018 collapse are profound, but not permanent. As the record over the past two centuries demonstrates, Kīlauea’s summit will erupt and collapse again (and again), repeatedly transforming the summit geometry and appearance in the process.

by Big Island Video News10:01 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - In this week's article, scientists explain how a story is told on the surface of Kīlauea's new landscape.