(BIVN) – The USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory continues to monitor Hawaiian volcanoes and earthquakes and issue regular updates, despite the spread of the COVID-19 virus and the governor’s stay at home order. “Through telework and other adaptations, HVO will maintain monitoring networks and continue analysis of incoming data,” a recent website update reads. “Field crews will visit critical stations as needed to maintain required quality and functionality of the network. All work will follow federal government guidelines to ensure public safety and the safety of our staff.”

This week’s Volcano Watch article, concerning “water, ash, and the great unknown of explosive volcanic eruptions”, was written by Johanne Schmith, an Associate Postdoctoral Researcher funded by the Carlsberg Foundation Internationalisation Fellowship of Denmark.

The presence of water in Halema‘uma‘u has sparked an important discussion about what the pond means for future eruptions at Kīlauea Volcano. There are no written records of water at the summit, so to guide the discussion we need information about magma-water interaction from deposits of the past.

But how can we get that information? I set out to answer this very question some years ago, and like many scientific quests, it started with a frustrating discovery.

Sitting in my lab one defining afternoon, I was studying the explosive nature of Icelandic volcanoes at the University of Iceland. Our grain shape analyzer sat in its lavender box on the lab bench, humming loudly, as a pump ran my sample of volcanic ash through a water-filled tubing system.

The grains went through an inch-long lens in front of a camera with a high-pitched shutter clicking manically at 30 frames per second. The screen next to the instrument showed a live stream of images with black particles on a light grey backdrop. In the sample bag, these same grains looked like tiny dust specks, but magnified on the screen, they came to life as abrasive, glassy shards of volcanic ash.

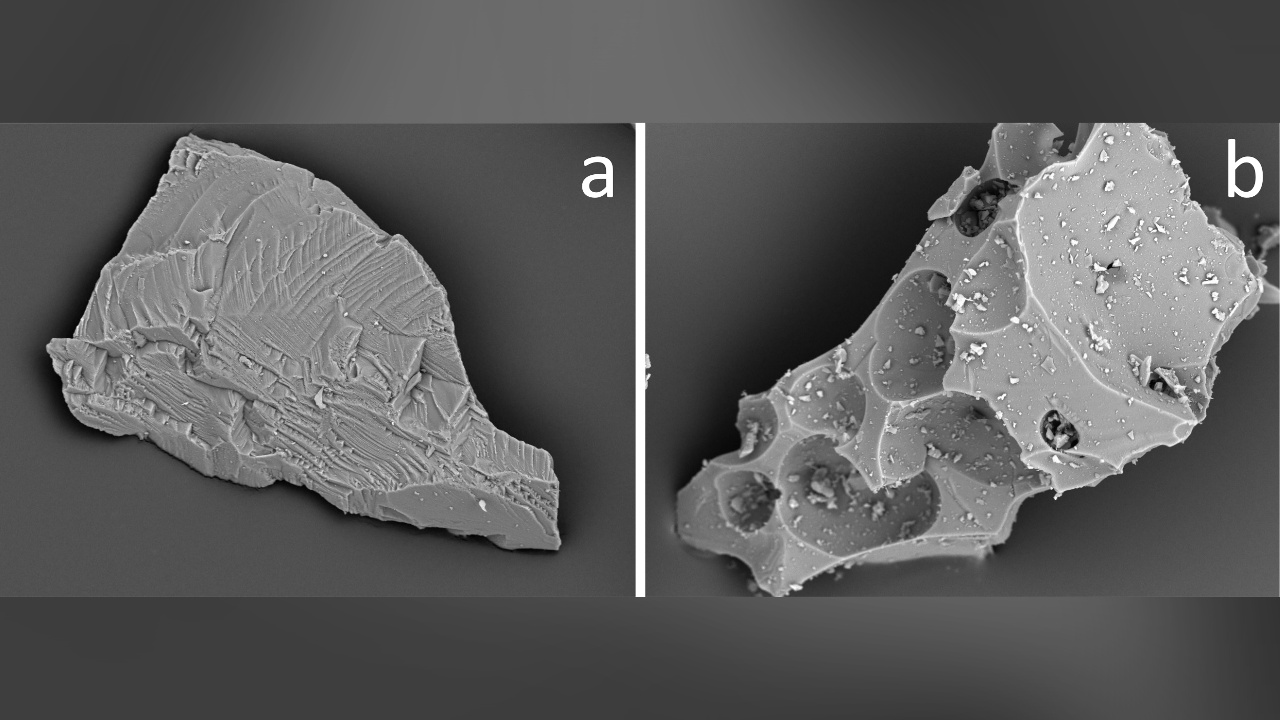

I had been in the lab for several hours that day and for weeks before that. My experiment built on the observation that ash generated by different types of volcanic explosions had different shapes. Ash from explosions caused by the expansion of magmatic gasses looked like tiny pieces of frozen foam with broken bubble walls. Ash from explosions in which hot magma interacted with liquid water looked like broken glass shards—dense and blocky.

This distinction was first observed in the 1970’s using big, expensive electron microscopes to view a small selection of grains. During my study with the new shape analyzer, however, we had the opportunity to get information on many thousand grains all at once, and I intended to use that to characterize some puzzling big ash deposits in Iceland, and to look for a link with magma-water interaction.

When the aggravating shutter clicking finally stopped, I pressed “export data” on the screen and ran to my desk to get the first peek at my achievement. I held my breath as the computer worked to plot results from all 20,000 grains, and then gasped in disbelief. My plot came out with grain shapes all over the place with no systematic groupings at all. I tried another sample, then one more and yet another, and I felt crushed! Many months of hard work seemed useless.

After days of checking my instrument setup, the quality of my data, and digging through a lot of scientific papers, I finally had an idea. The old experiments had characterized only a few grains, so perhaps something was missing in the classification scheme. So, I went back to my photos of individual ash grains and started to classify their shapes according to how much they were influenced by broken bubbles and consequently by magmatic gas expansion.

The grains weren’t just foamy or dense. Instead, I saw a spectrum of shapes, from blocky shards with dense glass and no bubbles, then blocky shards with a few isolated bubbles, to progressively more foamy grains. This was exciting!

Over the following weeks I worked to put this new information into a classification diagram. I collected new samples from different types of explosive eruptions for which I already knew if water was involved or not.

Some lab sessions later, I once again held my breath in front of my computer, but this time it worked! There was a predictable and systematic difference to the test samples. The Icelandic ash turned out to be the result of both magmatic gas expansion and magma-water interaction. We now have a more flexible way to characterize how water influences volcanic eruptions just from looking at the shapes of tiny ash grains.

I am now in Hawaiʻi, collecting samples of ash from Kīlauea to figure out what role water has played in past summit eruptions. Results will be discussed in a future Volcano Watch, so stay tuned!

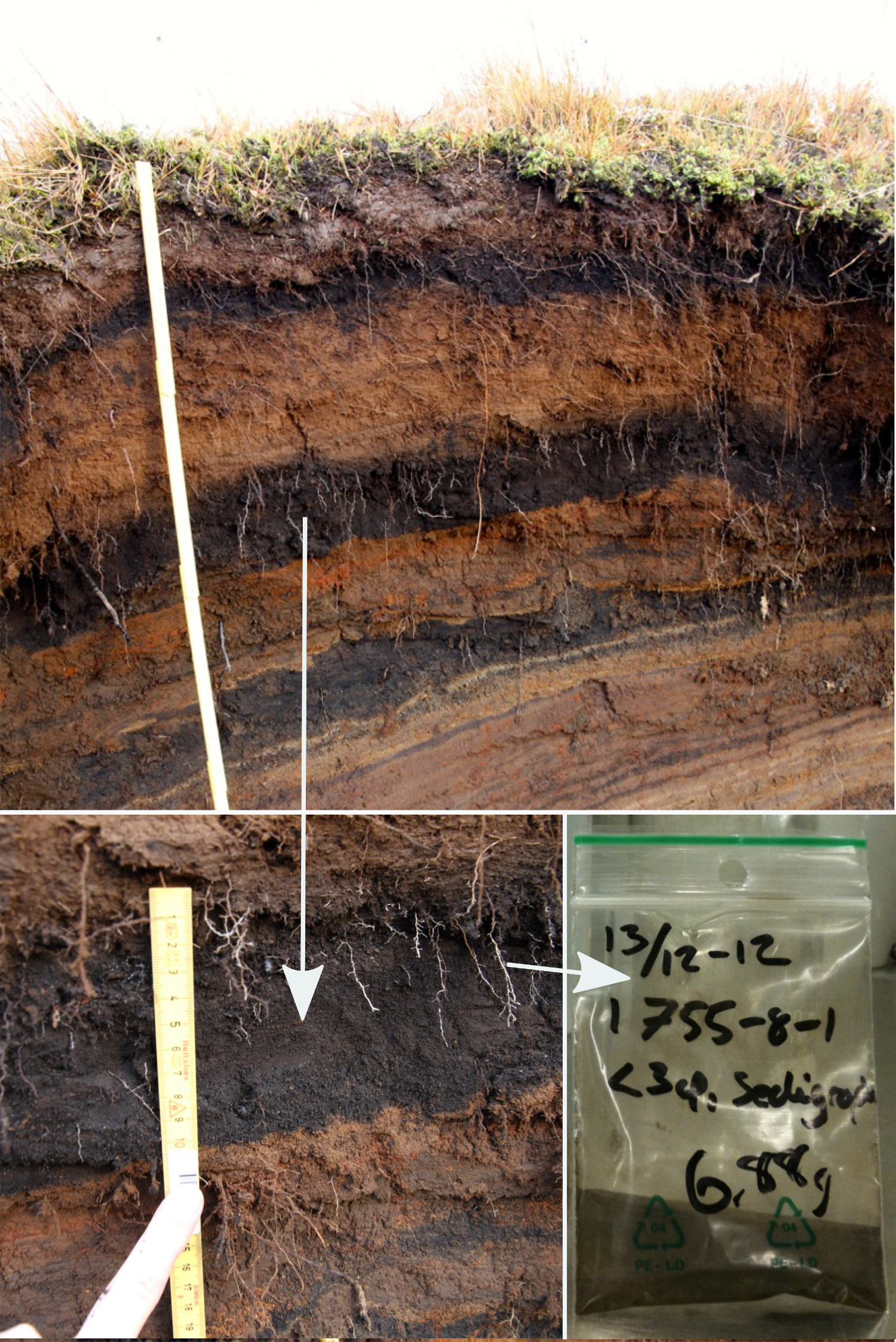

This section of brown Icelandic soil (top) contains 800 years of ash deposits erupted from five different volcanoes. The black layers, 5-10 cm (2-4 in) thick, are from Katla Volcano. A white arrow points to a closeup of the 1755 Katla ash deposit (lower left). The ash looks like specks of dust in the sample bag (lower right), but microprobe imaging reveals how complex the grain shapes are. Photos by J. Schmith.

by Big Island Video News8:52 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI ISLAND - Scientists are collecting samples of ash from Kīlauea to figure out what role water has played in past summit eruptions.