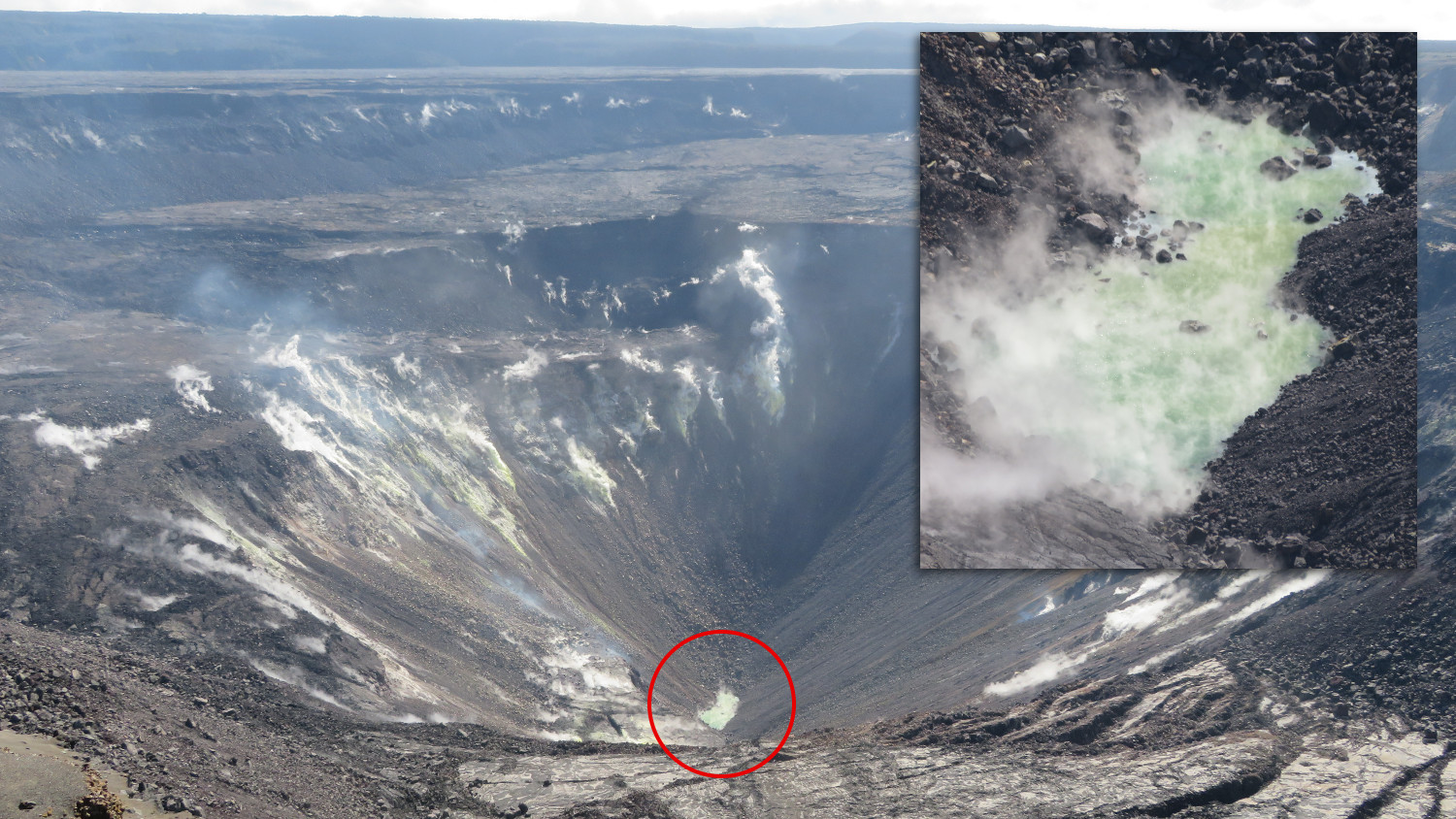

(BIVN) – As the water level of a new, green pond at the Kīlauea summit crater continues to rise, scientists are keeping a close eye on the volcano.

On a recent episode of Island Conversations on KWXX radio, Sherry Bracken sat down with USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory geophysicist Jim Kauahikaua for an in-depth discussion on the hot pond in Halemaʻumaʻu.

Bracken kicked off the talk by asking Kauahikaua where all that water is coming from?

“The water level is rising, slowly,” Kauahikaua said. “We can’t get real accurate measures of how fast it’s moving but we have a couple of indirect measures that suggest it’s rising at about, maybe, a yard a week.”

“The water is there possibly for two reasons,” he continued. “One is that it’s just rainfall collecting down there, in which case that should wax and wane with rainfall. The other is that this is actually the water table that was there, at a higher elevation, but got dragged down with the collapses of 2018. And it is now just, basically, rebounding after the collapse. It’s coming up to its former level, slowly.”

“So far, because the water level is rising steadily, and that it’s colored so it’s not like pure rainwater, the evidence is sort of leading towards ground water rebounding from the 2018 collapse,” Kauahikaua said. “From our observations it looks like it’s steadily rising, as opposed to going up and down with rainfall.”

Later in the interview, Kauahikaua explained how USGS has “a research drill hole that is about half a mile south of Halemaʻumaʻu, and so we know the water level in that well. And the lake will have to rise another 50 or so yards to be in hydraulic equilibrium with the water. So, if our hypothesis is correct that it’s groundwater that’s rebounding, that lake should rise to about that same level and then stall or stay there.”

Bracken also asked about the milky, green color of the water pond, and wondered what are the implications?

“Until we get a sample of it, we can’t say for sure,” Kauahikaua said. “But there are many lakes within volcanic craters around the world and they have a similar color and we think that’s due to absorption of sulfur gas. We’ve been measuring very low sulfur dioxide emission rates in the crater since the collapse last year. One possibility is some of that SO2 is being scrubbed out by the water. It’s soluble in water. So the water may be very acidic because of that sulfur content. We are working on some proposals for getting a water sample, either with a helicopter or a drone. We’re working very closely with the National Park to see what will work for everybody.”

The water is also hot. “We do have an infrared camera that we’ve been using,” Kauahikaua said. “About a week or so ago we trained that on the water lake and it appeared to have a temperature of about 70 degrees centigrade or about 160 fahrenheit. That may be a minimum temperature, because the water is so far away from the camera there’s some absorption in the atmosphere. But it’s clearly hot.”

It has been reported that this is the first time such a water pond has been observed at the Kīlauea summit in recorded history. Bracken asked the HVO geophysicist about clues – geological or oral histories – that indicate water ponds were present in the past.

Kauahikaua answered that “Don Swanson has been working on very detailed studies about how the caldera formed and what its history was, what happened from deposits that are around the caldera. He found that the caldera formed several centuries ago by a big collapse and it was followed by probably three centuries of intermittent explosive eruptions.”

“In studying those eruptions, while working with other colleagues, he found one possible culprit for why some of the eruptions were explosive, at least, was that the magma that was coming up from depth into the caldera may have come up so quickly into a shallow water lake that the magma fragmented and produced these very big explosions as water was flashing into steam.”

“That’s why we are not quite sure what hazards are posed by just the existence of the water lake,” he continued. “We know that there has been a shallow groundwater table under the summit for probably centuries now, and even in the last two centuries there have been many eruptions that occurred within the caldera that have not been explosive. So, we think that based on those older studies – and that based on what we know of the recent history of Kilauea – that two things that must occur before eruptions will go to big explosivity. That is: magma rises very quickly, which we haven’t seen before the last two centuries. And this water lake. Now, we’re getting a water lake, but it still isn’t enough to have explosive eruptions.”

“Are the scientists concerned that there could be that kind of really disastrous explosion,” Bracken asked, “because some of the headlines we have seen since the water was spotted made it sound like we were imminently waiting for a very explosive eruption. But I don’t get that sense from you and the other scientists, but let’s just make sure we’re crystal clear about what to expect.”

“We expect the water lake to keep rising,” Kauahikaua answered, “and until we have some information about very rapid magma ascent, were not very worried. The history of Kilauea… has been relatively moderate magma rise. We might get some fountaining. Most of those eruptions started relatively slowly, even for example Kilauea Iki, which had those very high fountains back in 1959. It started out as a fissure eruption, just pushing lava down into the deepest part of that crater. That kind of moderate magma rise, or magma ascent velocities, probably are slow enough that any water that is contacted will just slowly turn into small amounts of steam and basically insulate itself from mixing with more ground water.”

by Big Island Video News9:54 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory geophysicist Jim Kauahikaua talks about the rising, hot water pond in Halemaʻumaʻu crater.