(BIVN) – On February 7, a Magnitude 4.6 earthquake occurred roughly 50 miles offshore of Hawaiʻi to the south southwest. The event did not generate a tsunami, emergency officials say, but was strong enough to be felt all over the Big Island. It was the strongest earthquake since the summer 2018 eruption of Kīlauea Volcano.

In this week’s Volcano Watch article written by U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates, the cause of the offshore earthquakes is examined.

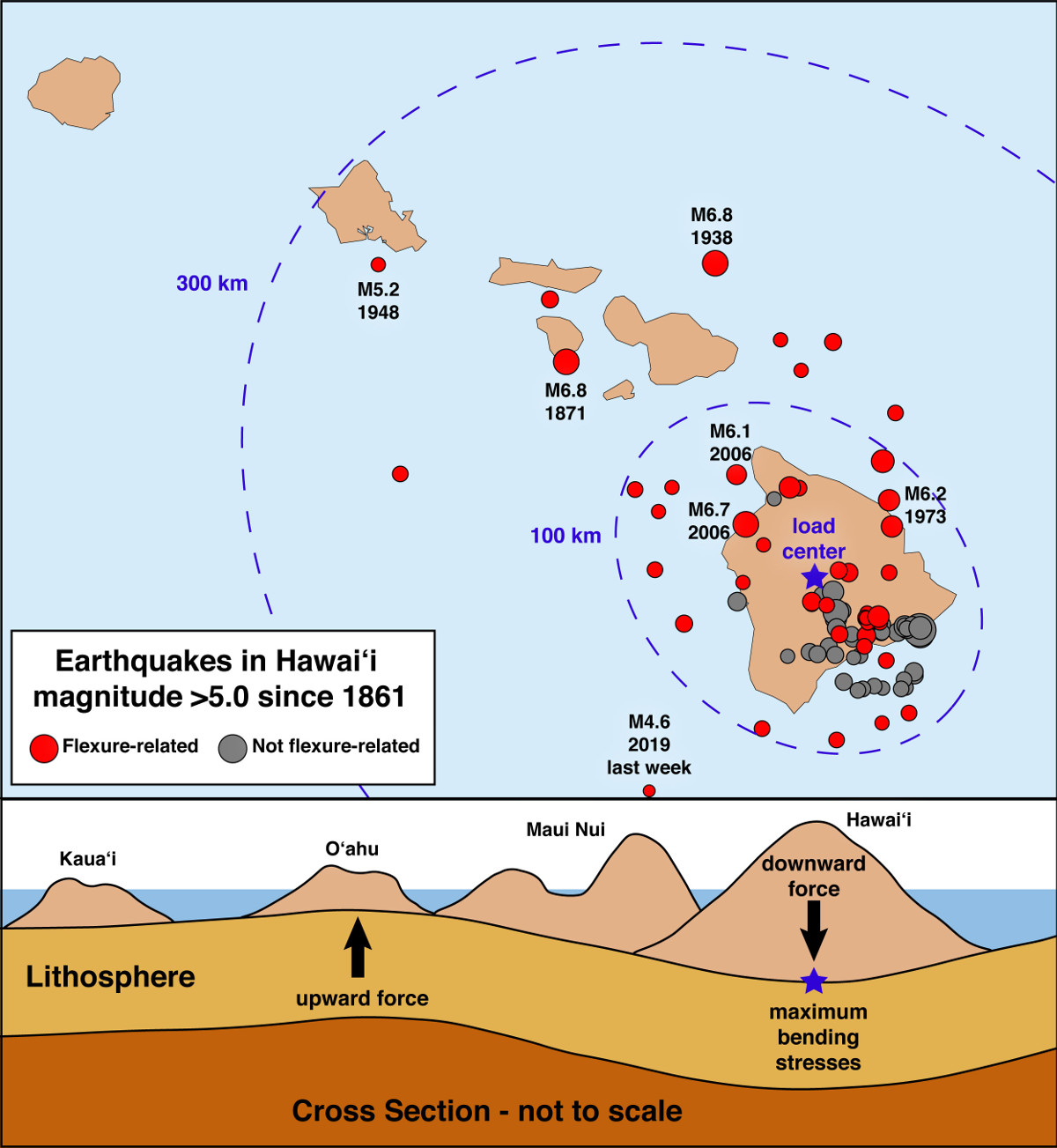

Many of the earthquakes in Hawaii that extend offshore and up the island chain are due to plate bending, or flexure. The upper panel shows magnitude-5 and greater earthquakes since 1861, with some notable events labeled. The area of maximum flexural stress is within about 100 km (62 mi) from where the Island of Hawaiʻi loads the plate, but also extends about 300 km (186 mi) northward, as far as O‘ahu. The lower graphic is a cross-section depicting how the Hawaiian Islands rest on Earth’s lithosphere and cause it to bend. Credit: B. Shiro, USGS HVO.

Why do some Hawaii earthquakes occur so far offshore?

Earthquakes in Hawaii are intimately related to the volcanoes. In addition to helping scientists track moving magma, sometimes they happen simply because the earth under the island chain gets bent out of shape.

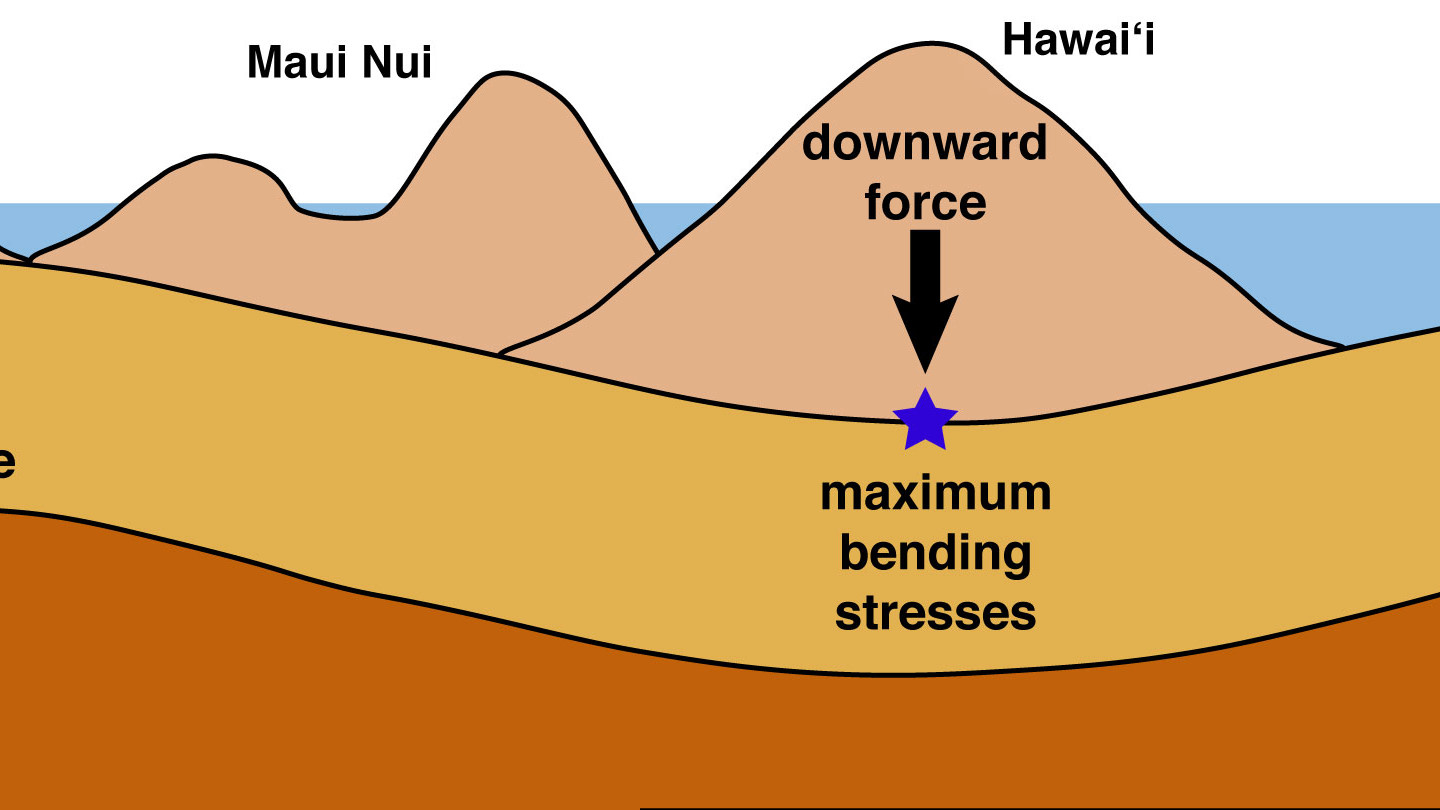

Earth’s tectonic plates are made of the lithosphere, which is a mostly rigid layer extending from the crust into the upper mantle. As the Hawaiian Islands ride on top of the Pacific Plate, their immense weight bends, or flexes, the lithosphere. Like a bowling ball resting on a soft mattress, this bows the lithosphere downward in a moat-like depression centered on the main loading center under the Island of Hawai‘i. This results in stresses that can lead to earthquakes.

Seismologists call these events “flexural earthquakes” to reflect their cause (plate bending). The massive Island of Hawai‘i produces the largest force on the lithosphere due to its relatively young age, which results in forces on the underlying lithosphere that have not yet evened out.

The zone of maximum bending stress from this load extends about 100 km (62 mi) offshore from the island. As the plate re-adjusts back to a neutral position, it results in a raised bulge in the lithosphere that extends around O‘ahu about 300 km (186 mi) away. This is why earthquakes occasionally happen so far from the main area of seismic and volcanic activity on the Island of Hawai‘i.

There have been two examples of offshore flexural earthquakes in the past month. They include a magnitude-3.7 event on January 21, which occurred about 240 km (149 mi) east of the Island of Hawai‘i, and a magnitude-4.6 event on February 7, about 84 km (52 mi) southwest of the island.

The January event was too small and distant for anyone to feel. But the February earthquake produced shaking intensity up to VI on the Modified Mercalli scale, and was reported by 115 citizens from Hawai‘i, Maui, and O‘ahu, up to 370 km (230 mi) from the epicenter. It was the largest earthquake felt in Hawaii since a magnitude-4.4 earthquake shook the Island of Hawai‘i on August 9, 2018.

Most earthquakes felt beyond the Island of Hawai‘i are presumed flexural earthquakes based on their estimated locations. Some historical examples include the magnitude-6.8 Lāna‘i earthquake on February 19, 1871; magnitude-6.8 Maui earthquake on January 22, 1938; magnitude-5.2 O‘ahu earthquake on June 28, 1948; magnitude-6.2 Honomu earthquake on April 26, 1973; and magnitude-6.7 Kīholo Bay and 6.1 Māhukona earthquakes on October 15, 2006.

Flexural earthquakes are sometimes called “mantle earthquakes,” reflecting the fact that they often occur at depths within the Earth’s upper mantle rather than within the crust. Seismic waves travel more efficiently through the mantle compared with the crust. This is one reason why mantle earthquakes can have widespread and sometimes damaging effects, especially as their sizes can exceed the magnitude-6 range.

Thankfully, lithospheric flexure produces earthquakes in Hawaii less frequently than those directly related to active volcanism. Each year, the U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) records tens of thousands of earthquakes on and near Hawaiʻi Island’s active volcanoes, compared with only a few hundred offshore flexural events.

The locations and magnitude parameters of earthquakes far offshore are not as well-constrained as events closer to the land-based seismic monitoring network. This is one reason why it’s more difficult for scientists to determine precise locations and depths for earthquakes that happen far from the islands. Nevertheless, any type of earthquake can have hazard implications, so HVO maintains a constant vigil and closely monitors seismic activity in Hawaii.

The next time you feel an earthquake, even if you’re far from it, we encourage you to submit a felt report via the USGS Did You Feel It? website. We also invite you to track earthquakes on HVO’s website.

by Big Island Video News11:51 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAIʻI ISLAND - Scientists say many of the earthquakes in Hawaiʻi that extend offshore are due to plate bending, or flexure. The events are also called "mantle earthquakes".