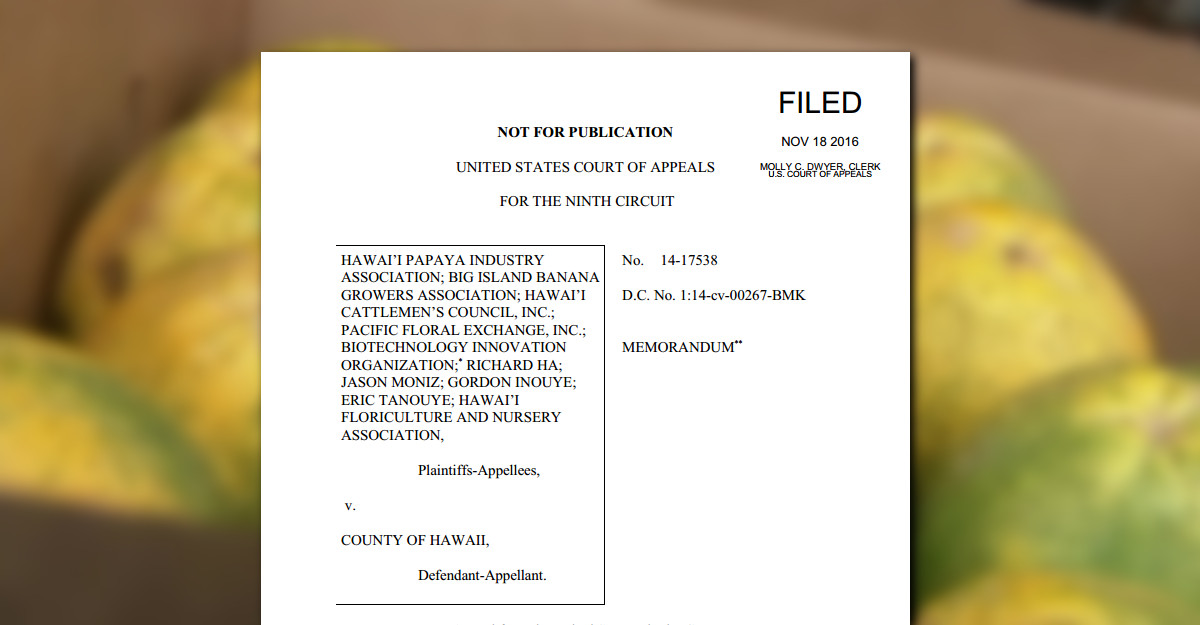

HAWAII ISLAND – A federal appeals court has sided with supporters of GMO, or genetically modified organisms, by affirming an earlier district court ruling in their favor.

Chief Circuit Judge Sidney Thomas and Circuit Judges Mary Murguia and Consuelo Callahan on November 18 held that the Hawaii County Ordinance banning the cultivation and testing of genetically engineered (GE) plants is preempted by the federal law as well as state law.

Bill 113, passed by the county council and signed into law by Mayor Billy Kenoi (as Ordinance 13-121) in 2013, banned “open air testing of genetically engineered organisms of any kind” and “open air cultivation, propagation, development, or testing of genetically engineered crops or plants.”

A group of Hawaii-based farming associations and prominent supporters of GMO technology took the county to court over the matter.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Barry Kurren ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in November 2014. The county appealed.

Oral arguments were presented on June 15, 2016. Earthjustice attorney Paul Achitoff represented the county.

Oral arguments from June 2016.

The judges agreed that the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s Plant Protection Act (PPA) expressly preempts the county GMO ban:

Under the PPA, “no State or political subdivision of a State may regulate the movement in interstate commerce of any . . . plant, . . . plant pest, noxious weed, or plant product in order to control . . . , eradicate . . ., or prevent the introduction or dissemination of a . . . plant pest, or noxious weed, if the Secretary has issued a regulation or order to prevent the dissemination of the . . . plant pest, or noxious weed within the United States.” 7 U.S.C. § 7756(b)(1). The Ordinance is therefore expressly preempted if three conditions are met: (1) the local law must regulate “movement in interstate commerce,” (2) it must be intended to “control . . . , eradicate . . . , or prevent the introduction or dissemination of a . . . plant pest, or noxious weed,” and (3) APHIS must regulate the plant at issue as a plant pest or noxious weed. See Cipollone v. Liggett Grp., Inc., 505 U.S. 504, 516 (1992) (Congress’ intent to preempt state and local law may be “explicitly stated in the statute’s language or implicitly contained in its structure and purpose”) (internal quotation marks omitted). Each condition is met here.

For the same reasons set forth in Atay, the County of Hawaii’s Ordinance satisfies all three conditions for express preemption. First, the Ordinance regulates “movement in interstate commerce” because it regulates the dissemination of plants and seeds from fields, which implicates interstate commerce. See 7 U.S.C. § 7711(a). Second, the Ordinance was passed in order to “control . . . , eradicate . . . , or prevent the introduction or dissemination of a . . . plant pest, or noxious weed.” Id. § 7756(b)(1). An express purpose of the Ordinance is to prevent the spread of GE plants, and it implements this charge by banning most planting and testing of GE plants. HCC §§ 14-128, 14-130, 14-131. Third, APHIS has issued regulations 4 in order to prevent the dissemination of the class of plant pests at issue, GE crops. See 7 C.F.R. Part 340.

We conclude that the Ordinance is expressly preempted by the PPA to the extent that it seeks to ban GE plants that APHIS regulates as plant pests.

The court also affirmed the county Ordinance is impliedly preempted by state law.

We have held that federal law preempts the Ordinance in its application to GE plants that APHIS regulates as plant pests, but not in its application to federally deregulated, commercialized GE plants. However, we find that Hawaii state law impliedly preempts the Ordinance in its remaining application to commercialized GE plants.

As explained in Atay and Syngenta Seeds, Inc. v. County of Kauai, Nos. 14-16833, 14-16848, Hawaii courts apply a “‘comprehensive statutory scheme’ test” to decide field-preemption claims under HRS § 46-1.5(13), such as that made by the GE Parties here. Under this test, a local law is preempted if “it covers the same subject matter embraced within a comprehensive state statutory scheme disclosing an express or implied intent to be exclusive and uniform throughout the state.” Richardson v. City & Cty. of Honolulu, 868 P.2d 1193, 1209 (Haw. 1994). Courts frequently treat this test as involving several overlapping elements, including showings that (1) the state and local laws address the same subject matter; (2) the state law comprehensively regulates that subject matter; and (3) the legislature intended the state law to be uniform and exclusive. However, as is true of our federal preemption analysis, the “critical determination to be made” is “whether the statutory scheme at issue indicate[s] a legislative intention to be the exclusive legislation applicable to the relevant subject matter.” Pac. Int’l Servs. Corp. v. Hurip, 873 P.2d 88, 94 (Haw. 1994) (internal quotation marks omitted).

As explained in Atay, Hawaii has established a comprehensive, uniform, and exclusive statutory scheme to address the threat posed by introduced, potentially harmful plants, and has delegated authority to the Hawaii Department of Agriculture (DOA) to enact rules to that end. By banning commercialized GE plants, the Ordinance impermissibly intrudes into this area of exclusive State regulation and thus is beyond the County’s authority under HRS § 46-1.5(13) and preempted.4 See Atay, Nos. 15-16466, 15-16552.

The victorious plaintiffs / appellees are the Hawai’i Papaya Industry Association, Big Island Banana Growers Association, Hawai’i Cattlemen’s Council, Inc., Pacific Floral Exchange, Inc., Biotechnology Innovation Organization, Richard Ha, Jason Moniz, Gordon Inouye, Eric Tanouye, and the Hawai’i Floriculture And Nursery Association.

by Big Island Video News1:18 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAII ISLAND - Bill 113, banning GMO testing and cultivation on the Big Island, was thrown out by a federal court November 2014. The county did not win the appeal.