HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK – An explosion that rocked the summit of Kīlauea on Saturday evening serves as a reminder of the Big Island’s volcanic dangers, federal officials say.

The explosive event at lava lake “flung chunks of molten and solid rock onto the rim of Halema‘uma‘u Crater, turned night into day, and destroyed the power system for scientific equipment used to monitor the volcano,” the National Park Service said in a media release.

Park officials say the incident further justifies the National Park Service’s closure of the summit lava lake and Halema‘uma‘u Overlook, and the partial closure of about four miles of the 11-mile Crater Rim Drive and Crater Rim Trail. The closures have been in place since 2008 when the current summit eruption began.

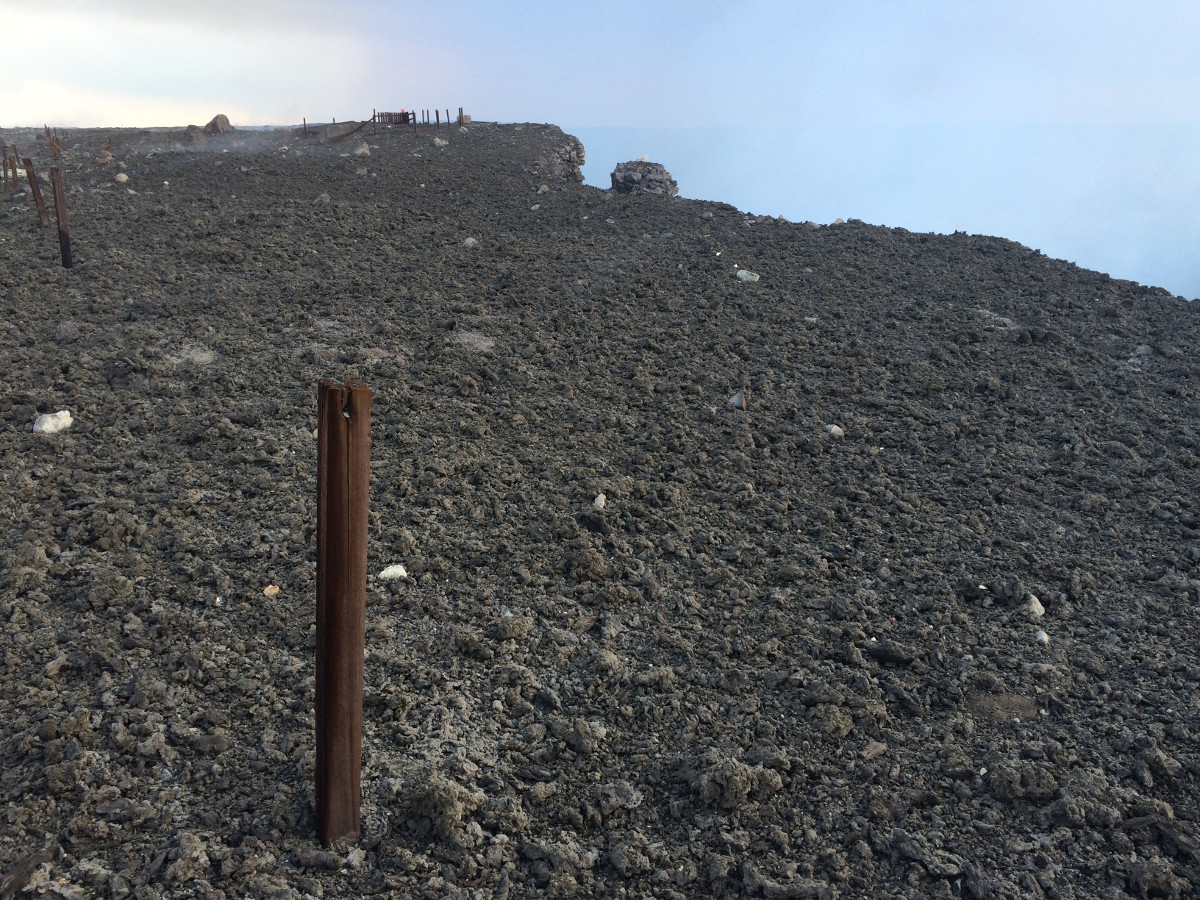

(USGS photo) The tephra deposit was thickest to the east of the former visitor overlook on the crater rim (shown here), where it formed a continuous layer.

“This type of volcanic explosion is not that uncommon at the summit of Kīlauea, and could have easily killed or seriously injured and burned anyone in the area,” said Park Superintendent Cindy Orlando in the release. “Despite the closure, people continue to trespass into the closed area, putting themselves and first responders at great risk,” she said.

The National Park tells this story from the night of the explosion:

Park ranger Tim Hopp was on routine patrol of the closed Halema‘uma‘u Overlook parking lot in his vehicle Saturday night. Suddenly, the dark sky lit up bright orange, “so surreal and bright you could read a book,” he said. He heard a violent and extremely loud sloshing sound from the crater. Fragments of volcanic rock, or tephra, were ejected from the volcano and rained down on his patrol vehicle as he cautiously left the area, respirator on. He noticed the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory equipment perched on the rim shooting off light as electrical wires burned. “It lasted about a half hour,” Hopp said.

An hour later, Hopp cited two individuals for sneaking into the closed area to get a closer look at the potentially lethal lava lake.”

The park has no plans to reopen the closed areas until the eruption from Halema‘uma‘u ceases, Superintendent Orlando says.

“Part of the mission of the national park is to provide safe access to active volcanism, and our emphasis is always on safety,” Superintendent Orlando said. “The view of the summit eruption is fantastic one mile away from the Jaggar Museum observation deck, and that’s as close as visitors can safely get,” she said.

USGS Volcano Watch

U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists agree with the National Park in their latest Volcano Watch article:

Kīlauea summit lava lake explosion reminds us of significant, ongoing hazards around Halemaʻumaʻu Crater

At 10:02 p.m., HST, on Saturday, August 6, a section of altered, thermally-stressed rock enclosing the Halemaʻumaʻu Crater lava lake detached from the vent wall and plummeted into the molten lava. Tons of rocky debris impacting the lake surface triggered a violent explosion of volcanic gas, incandescent spatter (blobs of molten lava), and pieces of solid rock that sent a jet of glowing debris skyward.

Within seconds, tephra (airborne volcanic rock fragments) began falling to the ground, blanketing the rim of Halemaʻumaʻu Crater—about 120 m (400 ft) above the lava lake surface—with a continuous layer of spatter and dense rock fragments that covered an area of about 50 m by 80 m (165 ft by 260 ft). In places, this tephra layer was up to 20 cm (8 in) thick. Almost certainly, anyone who had been near the crater rim in this area would have been killed or severely injured.

Trade winds influenced the trajectory of the fallout. So, while most of the tephra fell just east of the vent, pebble-sized debris also pelted the Halemaʻumaʻu Crater parking lot, about 500 m (0.3 mi) to the southwest.

As testimony to the heat and violence of the event, images captured two days later (posted at http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/ multimedia/index.php) show the blanket of spatter and solid rock fragments, with individual pieces up to 70 cm (28 in) across, on the crater rim.

Spatter that landed on a plastic case housing batteries and electrical components for a gravity monitoring instrument about 35 m (115 ft) from the rim of Halemaʻumaʻu melted the case and ignited a fire that incinerated its contents. The gravimeter itself survived, but is being systematically assessed for possible unseen damage. Other nearby HVO monitoring instruments remain operational.

Saturday night’s event was recorded by HVO web cameras, and HVO seismometers around Halemaʻumaʻu Crater detected a distinctive long-period signal related to sloshing of the lava lake set in motion by the rockfall. Following the 10:02 p.m. event, the lava lake surface remained agitated for a few hours, something also observed following past rockfall-triggered lava lake explosions.

Late-night visitors at the Jaggar Museum Overlook in Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park likely witnessed a dramatic and rapidly ascending bright orange glow as the explosion cloud rose above the summit vent rim. They might have also heard a low rumble followed by a loud boom as the vent wall gave way and impacted the lava lake. Diners at Volcano House Hotel, 3.5 km (2.1 mi) across the caldera, reported seeing an especially bright glow above the east margin of the lava lake. The distant glow was also noted by residents of nearby subdivisions.

In the aftermath of the event, HVO scientists and University of Hawai‘i colleagues carefully mapped and sampled the debris field before rain and wind could take a toll on the deposit. Analyses of the tephra may provide insight into how these lava lake explosions happen and what conditions favor their occurrence—information that could enable HVO to quantify the probability of future events and the likely range of dangerous impacts.

Rockfalls and the resulting lava lake interactions that produce a severe hazard are challenging, if not impossible, events to forecast. To date, HVO scientists have seen no evidence of precursory signals before an explosion, and the magnitude of the event likely depends on the location and size of the rockfall, the lava lake level at the time of the rockfall, wind velocity, and other dynamic factors.

Most rockfalls from the vent wall have occurred during rising lava lake levels, when large areas of the wall rock are heated and develop internal cracks due to expansion. But some rockfalls, like the August 6 event, occur after the lake level drops, possibly when the buttressing effect of the lake is lost, facilitating wall failure. These ideas are part of ongoing research examining the evolution of the summit vent since it opened in March 2008.

What is certain is that Saturday night’s explosive event reinforces our awareness of inherent dangers in the vicinity of an active lava lake in a deep crater. Residents and visitors alike are reminded to heed National Park Service and USGS advisories regarding volcanic activity and ongoing hazards.

by Big Island Video News11:47 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK (BIVN) - Both the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and USGS say the recent event at Kilauea is a reminder of the Hawaii Island's volcanic hazards.