HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK – The active lava flow heading towards Royal Gardens subdivision has a new name.

Scientists with the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory said in the weekly Volcano Watch article they are informally calling the eastern breakout the “61g flow”, in reference to the breakout on the east flank of Puʻu ʻŌʻō that gave birth to it. Episodes 61f (a north flank breakout on the June 27 lava flow, now inactive) and 61g both erupted early on the morning of May 24, 2016.

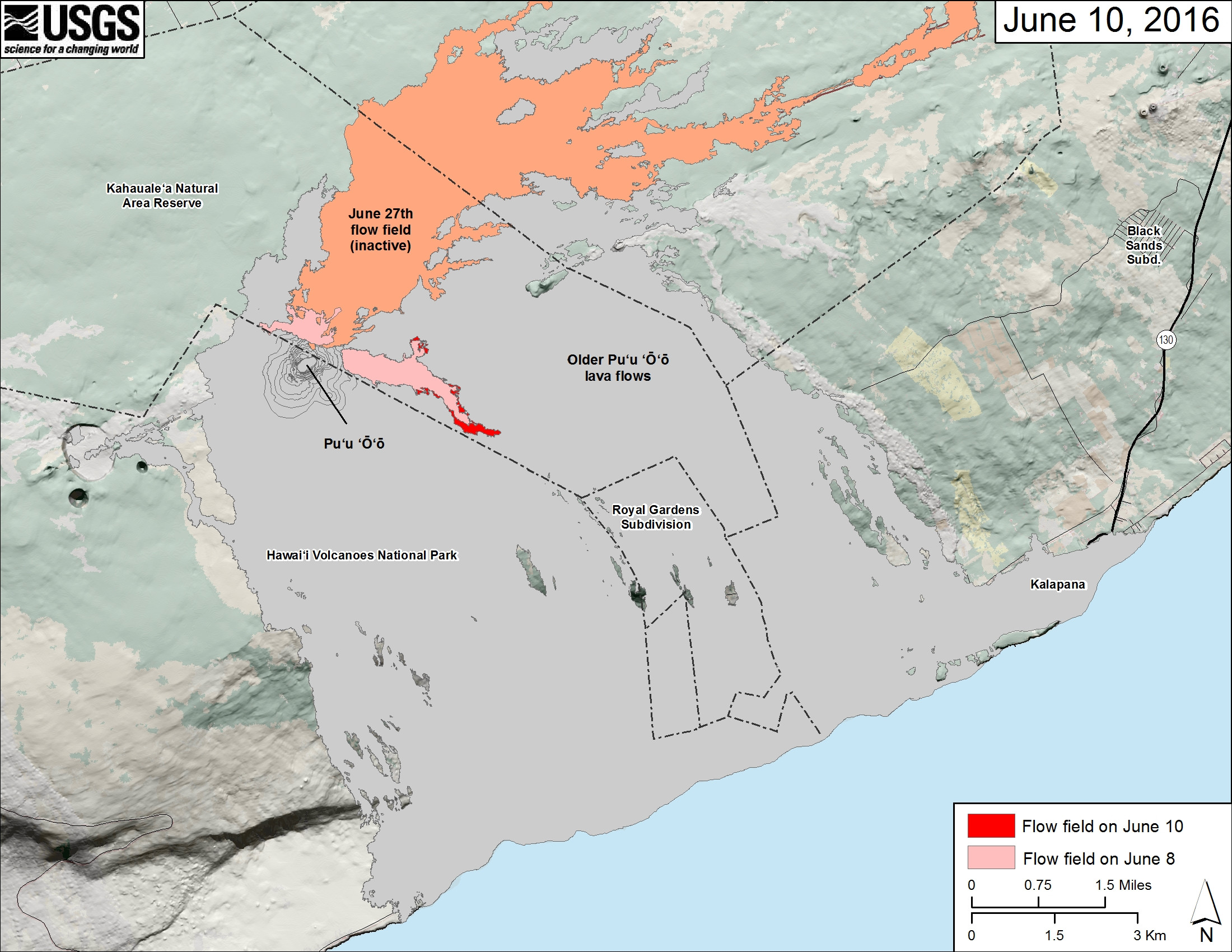

With the June 27 flow dead, the 61g flow has captured the outflow from Puʻu ʻŌʻō, and “is moving steadily southeast along, and just outside of, the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park boundary. The flow is contained within topography of older Puʻu ʻŌʻō lava flows and is headed for the northwestern corner of the long-abandoned Royal Gardens subdivision.”

Scientists also write that at its present advance rate, the flow could reach the Pulama pali in days to weeks. Beyond that, forecasts are difficult to make, USGS says, and “depends on the evolution of a tube system and constancy of lava supplied from the vent.”

VOLCANO WATCH: June 16, 2016

VOLCANO WATCHKīlauea Volcano’s new lava flows: the latest chapter in the dynamic history of Puʻu ʻŌʻō

Early on the morning of May 24, 2016, USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists were alerted by text message that a tiltmeter on the Puʻu ʻŌʻō cone on Kīlauea Volcano’s East Rift Zone had detected rapid change. Soon after, an HVO field crew reported that lava had broken out from the flanks of Puʻu ʻŌʻō. Tiltmeter data showed that the breakout likely began at 6:50 a.m., HST, resulting in a rapid deflation of the cone as magma burst forth from new vents.

HVO geologists were soon in the air to investigate the sudden—although not entirely surprising—change in activity at this long-lived eruption site.

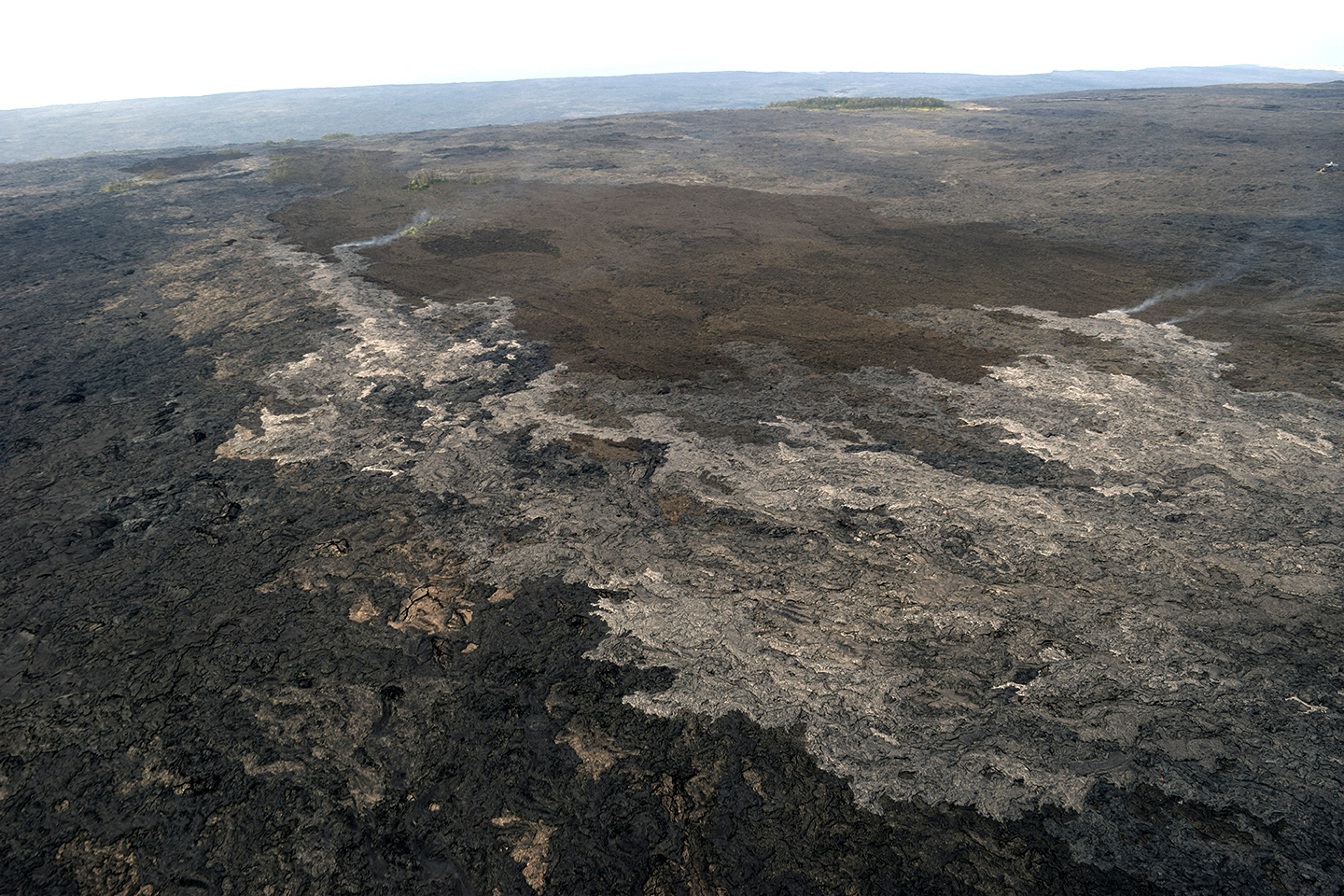

Once on scene, the geologists mapped and sampled two vigorous lobes of lava advancing from new vents on the north and east sides of Puʻu ʻŌʻō. Both lobes traveled atop older Puʻu ʻŌʻō lava flows, forming shimmering deltas of pāhoehoe channels, fingers, and toes. At the time, the two flows were about 1 km (3,300 yds) in length, too short to reach the forest on the north, but active enough to thrill tourists flying above the area.

Over the following days, activity continued from these breakouts—now called episodes 61f and 61g in the lexicon of HVO eruptive activity tracking. Each was developing nascent lava tubes and distributary channels that carried lava downslope, slowly extending their lengths and widths.

During this time, the “June 27th” lava flow field remained active in scattered areas within about 5–6 km (3–4 mi) northeast of the vent, a continuation of the activity observed in the same general area for the past year. Apparently, the supply of lava from Puʻu ʻŌʻō to the lava tube feeding the June 27th flow was not immediately starved by the new breakouts.

Now, however, only the eastern breakout is active—no lava has been sighted in the northern breakout or on the June 27 flow field since June 6. Clearly, the eastern breakout—informally called the “61g flow”—has captured most, or all, of the outflow from Puʻu ʻŌʻō. This is most likely because the 61g vent is at a lower elevation on the flank of Puʻu ʻŌʻō compared to the 61f vent and the older June 27th lava flow tube.

As of June 16, the 61g flow is moving steadily southeast along, and just outside of, the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park boundary. The flow is contained within topography of older Puʻu ʻŌʻō lava flows and is headed for the northwestern corner of the long-abandoned Royal Gardens subdivision.

At its present advance rate, the flow could reach the Pulama pali (a steep, lava mantled fault scarp on Kīlauea’s south flank) in days to weeks. If and when it reaches the coastal plain and then the ocean depends on the evolution of a tube system and constancy of lava supplied from the vent—variables that are difficult to forecast at this time.

This turn of events at Puʻu ʻŌʻō was not entirely unexpected. For weeks, an HVO tiltmeter on the north rim had shown steady outward tilting as magma accumulated in the subsurface reservoir system, pushing on the sides of the cone and the floor of the crater. Indeed, thermal webcam imagery showed the floor of Puʻu ʻŌʻō slowly lifting as the pressure increased from below and numerous small lava flows repeatedly erupted from vents within the crater.

The cone was clearly filling with magma, the crater floor responding like a piston and the flanks bulging outward. A new outbreak of lava was certainly possible, and, on May 24, it happened: flows 61f and 61g erupted from the flanks of Pu‘u ‘Ō‘ō.

Meanwhile, Kīlauea’s summit magma reservoirs have also been on a long run of inflation, punctuated by occasional DI (deflation-inflation) events. For some months now, we have considered the magmatic plumbing system of Kīlauea’s summit and upper rift zones to be pressurized and full, a condition ripe for change as stresses increase on the walls of engorged magma reservoirs.

Time will tell if and how other parts of Kīlauea respond to this pressurization.

For now, the recent activity at Puʻu ʻŌʻō is just the latest chapter in what long-time volcano watchers have observed for decades: Kīlauea’s complex and long-lived East Rift Zone eruption site is dynamic and always changing.

(USGS map) The area of the active flow field on June 8 is shown in pink, while widening and advancement of the flow field as mapped on June 10 is shown in red. The area covered by the June 27th flow (now inactive) as of June 2 is shown in orange. The Puʻu ʻŌʻō lava flows erupted prior to June 27, 2014, are shown in gray.

by Big Island Video News5:40 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

KILAUEA (BIVN) - In the weekly Volcano Watch article, USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists talk about the inactive June 27 flow, and the active "61g flow" heading towards Royal Gardens.